International Women’s Day: How does it link to sustainability?

Net Zero. Carbon Neutral. Headline after headline refers to these terms, as business after business makes pledge after pledge.

But, what does Net Zero really mean? How, and in what way, does Net Zero compare with Carbon Neutral? Is Carbon Negative really a thing? Does offsetting work or is it little more than greenwashing?

More importantly, if these grand pledges are for real, why does news of the climate crisis seem to get more serious by the day?

As a 2021 climate change risk assessment report, from think tank Chatham House, starkly highlights:

“If emissions follow the trajectory set by current NDCs [Nationally Determined Contributions], there is a less than 5% chance of keeping temperatures well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and less than 1% chance of reaching the 1.5°C target set by the 2015 Paris Agreement.”

Experts are still on the fence as to whether COP26 – widely touted as “our last chance” to tackle this global issue – is going to deliver solutions or simply make more promises it is yet to keep.

Even the Queen was recently reported as saying she finds all this talk and no action from world leaders ‘irritating’.

As Greta Thunberg highlighted at the last climate change conference, COP25, it’s worse than irritating – it’s dangerous:

“…I still believe that the biggest danger is not inaction. The real danger is when politicians and CEOs are making it look like real action is happening when in fact almost nothing is being done apart from clever accounting and creative PR.”

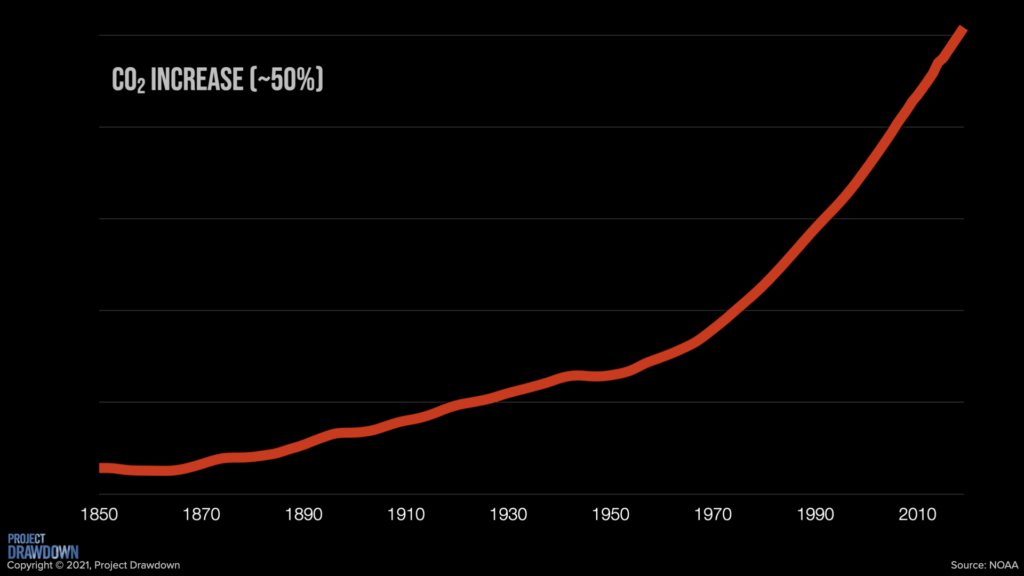

The rise of CO2

So, in the face of impending doom, at a time when an increasing number working in sustainability are questioning if all the work we do is actually working, we went in search of clarity on the Net Zero issue.

We found it in the form of Charles Redfern, founder and MD of Organico Realfoods, one of our trusted partnership brands that has just launched its ‘Better Than Net Zero’ policy.

We asked: Is it easy to get to Net Zero?

“Yes it’s blindingly easy. Just switch the fossil fuel tap off,” said Redfern, somewhat ironically.

Ironically, because this blinding easy solution is reliant on governments prioritising switching from fossil fuels to renewables.

So, in the meantime, we asked:

While we wait for governments to stop investing in fossil fuels, do business pledges matter? If so, what ones?

And can we as individuals do anything about the climate crisis. If so, what can we do?

In a nutshell, Redfern told us that once we’ve done our savings (i.e. consume a bit less of everything) and made a couple of switches (to a genuinely green energy supplier and ethical bank), the only real thing we can do is offset. Spoiler alert: this comes with its own set of issues.

So, we went further into the detail. And Redfern gave us a refreshingly honest account of the situation, as he sees it. We came away with purpose and clarity – and a reason to try.

Here’s why you should not give up, or give up hope:

“We have the recipe for the biggest clusterf*ck, ever. And that’s where we’re at.”

Live Frankly: First up, three easy questions. What is Net Zero? How is it different from Carbon Neutral? And is it really achievable for companies?

Charles Redfern: In its original form, when the term Net Zero was coined by scientists, it was used to:

“Describe scenarios when the entire atmosphere was, on balance, no longer building up greenhouse gases. Not a company or a country. The whole planet.”

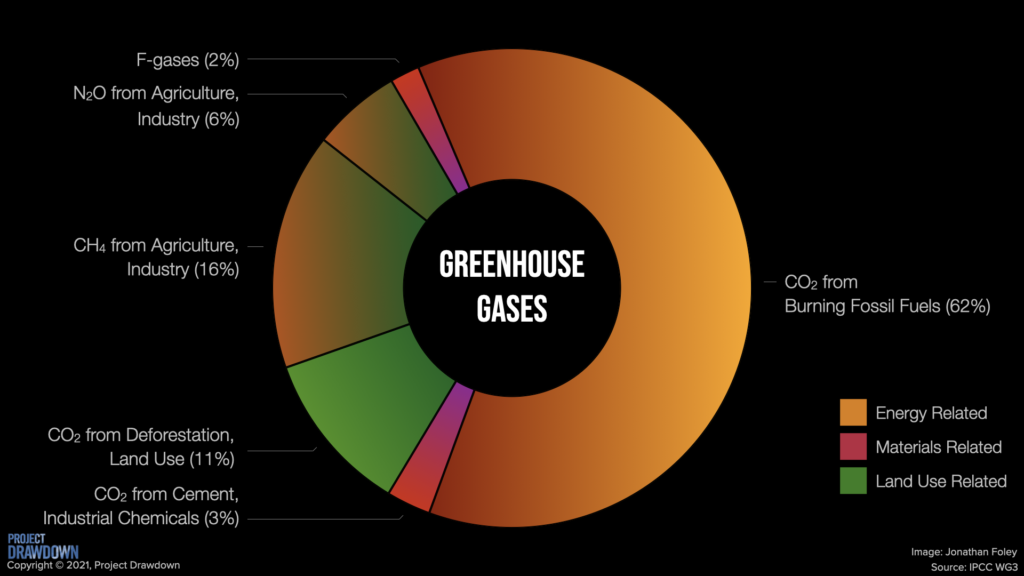

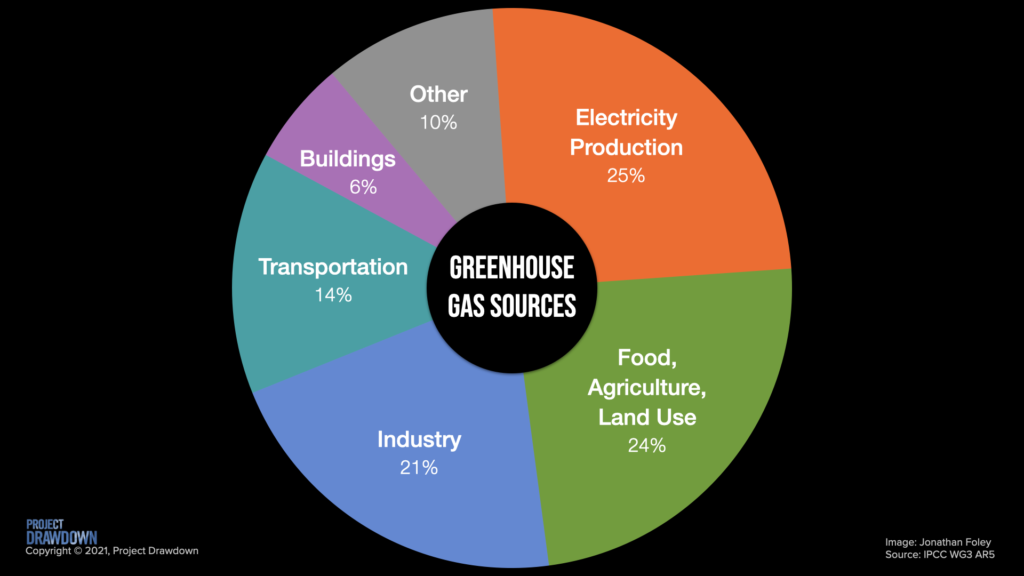

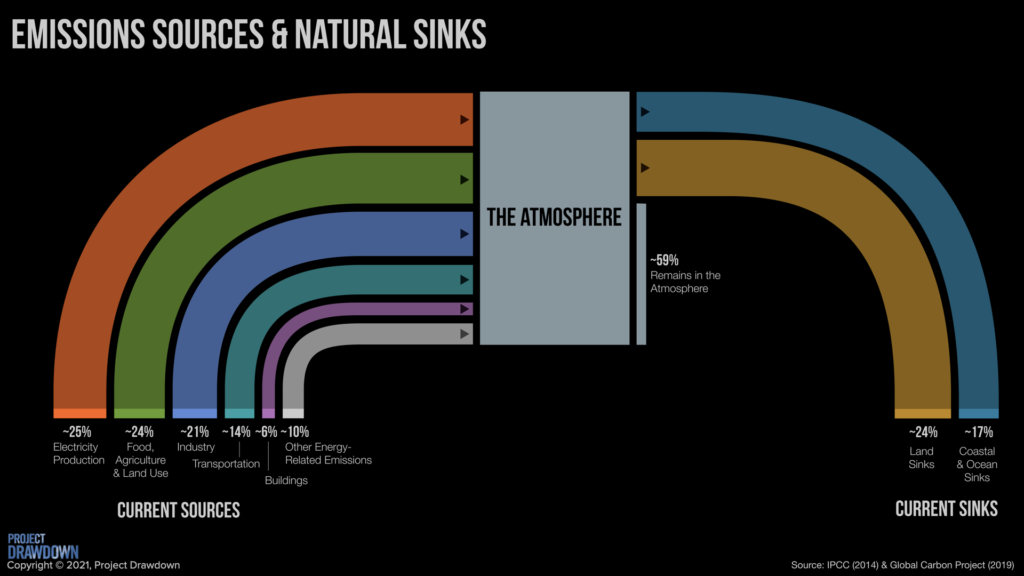

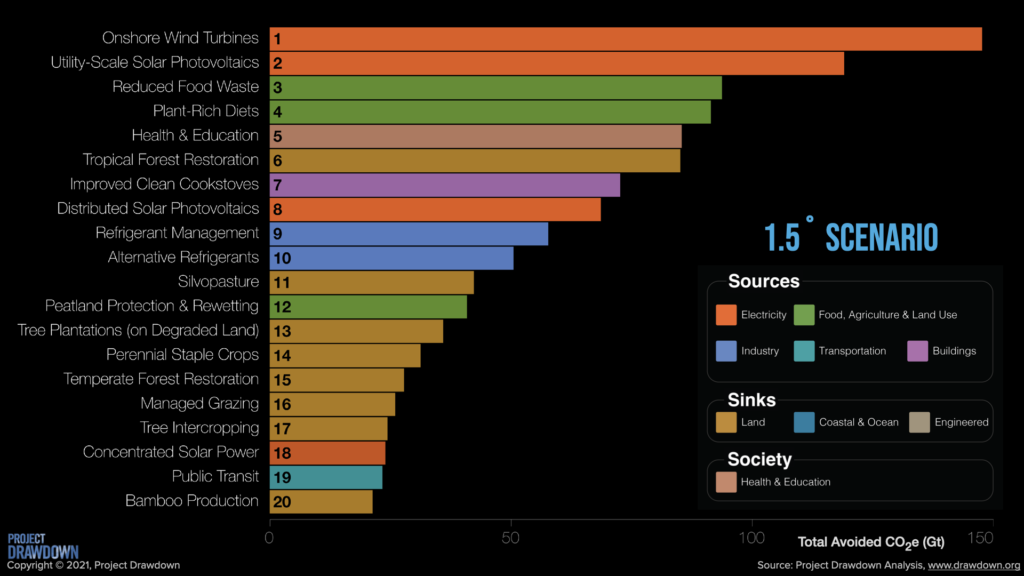

This involves reducing the world’s greenhouse gas emissions by around 90% and using carbon removal projects for the few remaining emissions, according to climate solutions charity Project Drawdown.

Net Zero does translate well at a country-by-country level and is a great COP26/Paris agreement target.

The goal is that every country aims for Net Zero and the planet is balanced.

But the reality is, dozens of governments need to agree about carbon change.

So, we have the recipe for the biggest clusterf*ck, ever. And that’s where we’re at.

For example, if every country has carbon limits to agree to, this means every country needs to take into account imported emissions as well as the ones they emit directly…

Woah. Maybe we were a bit ambitious with our first three questions. Let’s go back a step. What are “imported emissions” and why do they matter?

So, for example, in the last couple of decades the UK has reduced emissions due to de-industrialisation: we manufacture less.

But, we don’t consume less. We just import products rather than make them.

The reality is, with every product we import we import the emissions used to make them, too.

According to WWF data as much as 46% of UK emissions are produced abroad for the goods we import.

Got it. Any other emissions we need to take into account?

Yes. We need to consider our historic responsibility. This is all the carbon emitted since industrialisation – especially from the 1950s onwards.

Historic emissions sound weirdly pernickety, but they’re not. Again, to quote Project Drawdown:

“If a factory was dumping toxic sludge into a local lake, government agencies would order them to do two things—stop polluting the lake as quickly as possible and then clean up the pollution they already dumped there. Why is the atmosphere any different?”

So, for example, although China currently emits far more than Europe per annum, its historic footprint is much smaller and this needs to be factored into negotiations.

So, does it matter what we do at a company or individual level, when the problem is so huge?

In terms of the scale of the climate crisis, our Organico policy is a drop in the ocean and a total waste of time.

But, if every 10-person company in the world was doing what we’re doing, the world would be in a better place.

It’s hugely important that as many of us are as genuinely on-board as possible.

When it comes to the climate crisis, we’re all in this together. Everything we do – everywhere we go, the stuff we buy, the way we work – has a carbon price tag.

“We wanted to know where we were really at, not how good we could make ourselves look.”

OK. We’re on board. Organico say it’s ‘Better Than Net Zero’. What do you mean by this?

The tagline was used half in jest, picking up on the tendency of company PR departments to out-boast each other.

But, we’re pretty proud of what we’ve achieved.

We’re fortunate we had a very good starting point – we’re already in low carbon categories: Organico lines are entirely plant-based, and the Fish4Ever brand is a low-emissions product. Plus, all our products involve preserving food at the point of harvest, are long life and don’t require refrigeration – so there’s minimal waste.

But, we also knew we couldn’t assess our full impact without doing the proper maths. We wanted to know where we were really at, not how good we could make ourselves look. So, we employed a third-party consultancy to count all our emissions according to established CO2 accounting protocols.

Then we verified our findings with third-party certifiers and benchmarked ourselves against industry standards. For example, we benchmarked where we are against the route map produced by the British Retail Consortium – and, honestly, we’re streets ahead of the target dates and the objectives they lay out.

Essentially, when we say we are net zero, it’s for all the products we sell from cradle to gate – from the farm or sea up to the door of our customers plus all of the factories, warehouses and office administration in between.

So, you’re already ‘Better than Net Zero’ but many commitments are often projected into the future – Net Zero by 2030, 2040 or 2050. Is this OK or is this greenwashing?

If people are genuinely on the Net Zero path that can only be a good thing.

Many carbon emissions are not within a company’s control. This is the case with us. So, the pathway to most companies achieving Net Zero depends on the wider economy kicking our fossil fuel addiction – i.e. the government prioritising the switch from coal, oil and gas to wind, solar and other renewables.

However, if this is what a company’s policy is based on and the world economy doesn’t meet its targets – which is, unfortunately, a realistic prospect – what’s the company’s Plan B?

If there’s no Plan B, this is a huge problem with future promises. They are potentially lulling us into a false sense of security – and there’s no way of holding companies to account.

What about the companies staying quiet and not making any promises, at all?

It’s not the job of a company to solve climate change. It’s a job of a company to provide products or services in the marketplace.

The vast majority of companies, especially small ones that often live day-to-day, aren’t doing anything. That’s not stupid, nor mean. There’s currently no clear standard to follow and there’s no financial incentives. In fact, the opposite is true. It’s financially punitive, because there’s expensive consulting costs followed by expensive investments in decarbonisation projects or offsetting.

And, then you also risk being called out for greenwashing, even if you’ve done what you thought was best.

This, again, is why the government needs to be driving the transition. They need to set the parameters and incentivise businesses to be better.

“There is a legitimate concern that carbon isn’t the only metric that should be counted.”

If a company is Net Zero or Carbon Neutral, does that also make it ethical?

There is a legitimate concern that carbon isn’t the only metric that should be counted – we also need to take into account biodiversity, water retention, social responsibility etc.

This presents some interesting questions. For example, let’s consider organic and higher welfare meat production. Organic cows live longer, so do free-range pigs and chickens – so, they all have a higher carbon footprint than industrial produced meat. But, factory farming is linked to poor animal welfare and poor treatment of workers and wider pollution issues.

When it comes to all of this, we’re still in the infancy of working out what data needs to be taken into account and how it all fits together.

It’s said that the carbon calculator was a campaign from BP to deflect blame from the fossil fuel companies, and shift it onto individuals and companies. What’s your view on that?

The climate crisis issue is so urgent, we need to focus on that. If we focus on blame we’re not focusing on solving the problem.

We need to call out greenwash and be honest about poor practice. But, we need to draw lines in the sand and get everybody on-board with the transition away from fossil fuels. That has to be the priority.

OK. Lines drawn. Back to actions we can take. Is Net Zero the same as Carbon Neutral?

They’re pretty interchangeable at a company or individual level.

Globally, carbon emissions have continued to grow despite more and more organisations claiming to be carbon neutral or negative. This is because Carbon Neutral status can be achieved simply by offsetting. This practice clearly doesn’t reduce emissions.

Net Zero, technically speaking, is when companies and countries commit to prioritising the reduction of emissions as far as humanly possible first, and then use offsets or sinks to deal with the remainder.

Is it really possible to be carbon negative?

Yes and no. No, because your carbon is out there. Yes, if you offset.

Is offsetting good? Is it bad? Give us the lowdown.

Offsetting is when you attempt to balance out the carbon you emit. For example, you emit carbon by flying so you plant trees which can suck an equivalent amount of carbon out of the atmosphere.

At a company or individual level, it’s hard to be genuinely Net Zero without resorting to offsetting.

OK. So, what’s the issue with offsetting then?

There are some legitimate criticisms of offsetting. The main ones are:

Criticism #1: Offsetting doesn’t work

The biggest criticism is that you can’t put the genie back into the bottle – once carbon is out there it’s out there.

This isn’t strictly true. We can compensate for some of our emissions. Nature provides natural ‘carbon sinks’ i.e. the rainforests and the oceans soak up around 40% of the carbon we currently emit.

The Daguspta Review (and pretty much everyone concurs): “Large-scale and widespread investment in nature-based solutions would help us to address biodiversity loss and significantly contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation…”

So, planting trees can help.

Criticism #2: The rich can’t buy their way out of this one

The first criticism is mixed up with finger pointing. Essentially, it is rich countries – and within them, rich people – who emit the most. A lot of people aren’t happy at the idea that they might be able to emit what they like guilt-free.

Moral judgements aside, the very real issue is there isn’t enough compensation to go round. i.e. There’s not enough land in the world to plant the amount of trees that are needed to counteract global warming caused by human economies.

A recent Oxfam report showed that to offset the carbon of just four oil companies it would require the equivalent of all the farmland on the planet.

This is why offsetting alone isn’t the answer.

Criticism #3: Offsets aren’t guarantees of carbon removal

When it comes to offsetting the emissions you can’t reduce, there’s further issues. Offsetting relies on future predications, so there can be problems of over-counting, double accounting etc.

Planting trees is a popular offset option. Biodiverse forests (multiple species of trees and plants) are much more effective carbon sinks than monocrop forests (only one species of tree), but a lot of offsetting schemes plant monocrop forests. These might be a forest of timber trees, for example. These trees are likely to later be cut down for their wood. That then releases all the carbon that was meant to be stored.

We also saw earlier this year that some well-calculated offset forestry went up in flames. These forest fires are, in part, a consequence of global warming. Not only does the offset also go up in smoke, this smoke also increases the carbon in the atmosphere.

Essentially, offsets are not guaranteed to work in the future. This is why we need to reduce our emissions now.

Criticism #4: Offsets are unregulated

Then there’s the fact that offsets are an unregulated market. There are number of voluntary standards or certification schemes – the two best in my opinion are the Gold Standard and Verified Carbon Standard – but not everyone agrees.

We risk going down a rabbit warren here… essentially, at Organico we believe in third-party certification. However, there’s issues to iron out with certification to make offsetting truly impactful.

That’s a lot of criticisms. Do you use offsets at Organico?

Yes. At Organico we reduced our emissions wherever we could first – we put solar panels on our office roof and committed to buying shares or bonds in 100% renewable energy to help to fund the transition.

But, our organisation footprint is tiny at 0.6% of the total we calculated.

Company carbon emissions are typically divided into three ‘scopes’, and businesses need to consider all three:

Scope 1: direct emissions

These are sources you own and control as a business i.e. the vehicles you own and computers you use

Scope 2: indirect emissions – owned

i.e. the electricity provider you choose

Scope 3: indirect emissions – not owned

This includes emissions of all your products from the very beginning to the very end – beyond consumer use, right up to the point of disposal and waste (called ‘downstream’ activities).

Plus, it accounts for employee commuting and business travel (called ‘upstream’ activities).

Unsurprisingly, Scope 3 normally accounts for the bulk of a company’s real footprint, in some cases up to 90% of the total impact of businesses.

We can’t control the emissions in Scope 3. In our case, they are mainly from independent businesses in our supply chain who farm, fish and create the products. So, we influence these businesses where we can and we offset in the meantime.

Do you use certifications to validate your offsets?

Yes and no. Of course, the answer isn’t simple!

For our organisation footprint (Scope 1) we pay for a certificate for verified carbon withdrawal.

But, for Scopes 2 and 3, we were put off certification for two reasons. Firstly, it’s very expensive and we want our money going directly to mitigations. Secondly, it feels quite impersonal – you just buy into your chosen projects via a website.

Instead, we created two rules for ourselves.

Rule 1:

We will spend at least what we’ve saved on not going down the certification route on a well-established and well-managed reforestation scheme initiative with a good impact in terms of carbon sequestration and awareness of all the issues around tree planting. We found a brilliant reforestation charity, Eden Reforestation Projects, that plants trees in the tropics and works with local communities on poverty alleviation. The CO2 impact of trees is calculable. We’ve entered into a five-year contractual promise and aim to plant 500,000 trees in total. The first 200,000 are already paid for, so we’re well on the way.

Rule 2:

We will double pay. So, we also partner with the Environmental Justice Foundation to support their work on climate justice and climate refugees. Plus, we support Ecosystem Restoration Camps – an absolutely inspirational organisation that helps to restore totally degraded lands and soils. Both charities are very close to our own values, and are combatting some of the negative impacts of the world’s trade and food systems.

Final question, at an individual level how do we each play our part?

Even if as an individual you are very good, the broader economy is drenched in global warming impacts – mostly down to coal, gas and oil. So, protesting and making it clear to politicians that climate change is important is of supreme importance.

The work of Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion may backfire in terms of getting the wider public on-board but it has undeniably bumped climate change up the political agenda.

As for lifestyle style, generally cutting down consumption (including flights) and waste should be on all our radars. We can all support the move to renewable energy by purchasing our energy from a genuinely renewable energy supplier (Live Frankly: have we mentioned we’re sponsored by Good Energy?). But, a large number of us could go further: if you have savings or a pension, use them to back the energy transition and sustainability in general. In the world of food, we can all support organic products and opt for a more plant-based diet. (Live Frankly: here are the seven most impactful changes you can make).

To get a good idea of the real science, Mike Berners Lee’s How Bad are Bananas? is an essential read.

Project Drawdown offers brilliant lofty and academic reports, but also more easily digestible primer videos.

If you’re more about radio and spoken word download the “outrage and optimism” podcast – well worth a listen.

Finally, there’s some “lifestyle-based” carbon calculators that can be useful, including:

Phew. OK. Thank you for that. I’ll bookmark these and come back to them coffee in hand.

Interestingly, I was looking at the carbon footprint of a coffee the other day…

Ummm…

Let’s save that for another day.

Main image: Greenhouse Gas Sources, Project Drawdown