The best BBQ Delivery Boxes in the UK from small sustainable British Farms

Long Read: Written in collaboration with Fairtrade

“I think it was – and I’m criticising myself here as much as anyone else – perhaps shortsighted and arrogant to have been dismissive of certifications the way that we were,” admits coffee guru James Hoffman at the end of his Certifications Explained YouTube video, published earlier this year.

He adds: “It’s been quality, quality, quality, quality and maybe at the expense of some other stuff.”

At the request of Fairtrade, I’ve spent the last few weeks speaking with specialty coffee brands to learn more about sourcing and their views towards certifications.

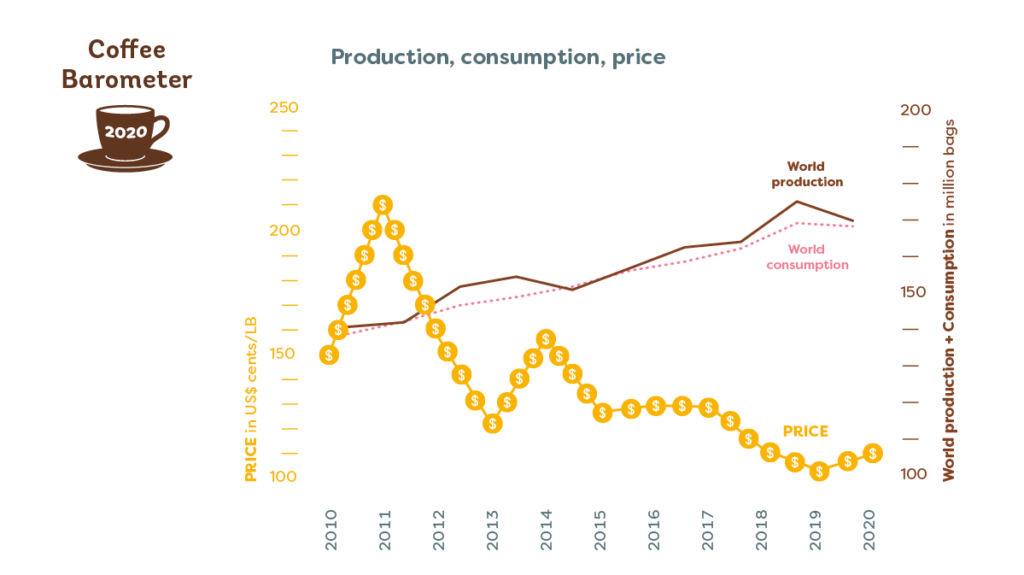

Over the last year, coffee prices hit a 10-year high, rising 78% within a year to just over $2.39/lb (£1.73/lb). But, while researching and writing this article, the coffee market crashed – historically so, by about 40%, with prices dropping to $1.61/lb.

So, the reality of an industry that appreciates the skilled labour involved in making good coffee but operates in a way that keeps coffee farmers at the mercy of an unpredictable market, hits home.

I have seen first-hand how precarious the situation of coffee farmers is. In 2019 I travelled to Kenya with Fairtrade to learn about a project that was working to empower women in coffee, for an article for the Independent.

“A lady with resources is empowered to say yes or no,” farmer Esther Chepkwony told me, then. I’m pleased to report Women in Coffee is still going strong today, giving 600 women more equality and control over their own lives.

This was at a time when the price of coffee was fluctuating around $1 per pound, which led to farmers struggling with low incomes and in extreme cases, poverty. The lives of the coffee farmers we met were far harder than the lush green landscapes of the Nandi Hills suggested they should be – and these were farmers benefiting from extra income provided by Fairtrade sales.

So, I understand the scepticism around certifications like Fairtrade. In fact, this is one of the reasons I went on the trip – to further my understanding of how ‘fair’ it really is. Three years later, I’m still on that complicated journey of unpicking supply chains. But, the question I now also ask is, how fair is the alternative?

What’s in a cup of coffee?

“When you have a cup of coffee, you’re part of something bigger – you’re part of somebody’s story,” says Fairtrade’s supply chain and programmes manager for coffee, Eleanor Deans.

This is a view I hear from coffee experts again and again.

“It’s not just a cup of coffee. There’s people all along the chain who have put their heart and soul into getting it to you,” says Nicole Ferris, MD of Climpson and Sons.

“One of the most impactful things I saw while I was in Honduras was a cupping table of samples being offered. Everybody on the trip from the UK chose the same coffee as their favourite and the guys who prepared the samples knew exactly which selection we were going to choose because it’s the sort of coffee they profile for UK buyers. They knew that was the kind of coffee we like,” says David Jameson, explaining the level of expertise required on the ground. He is founder of newly-launched Danelaw Coffee, and one of about 100 key graders (professionally licensed coffee tasters) in the UK.

We drink a reported 98 million cups of coffee a day in the UK. It is the second most popular drink only to water. Yet, how many of us take that moment to think of the people who have grown the main ingredient in our cup?

Truly, many of us don’t even know that coffee starts as a cherry, grown on a bush.

One consequence is that most coffee farmers today receive an estimated 3% of the cost of a cup of coffee sold in a coffee shop and many earn less than $2 a day.

There are some farmers who are able to command higher prices for specialty coffee. Some companies buy on Fairtrade terms (explained further down). Other companies choose to work with particular farms, known as the Direct Trade model (also explained below).

But, even when it comes to these interventions, the fact remains that too many farmers have little control over their pricing and have to rely on good intentions – as opposed to building their businesses and commanding a fairer price for their crop.

Specialty coffee and the Direct Trade model

Seeing the impact paying more for your coffee has is, of course, important to brands who want to be assured that they are benefiting the farmers they partner with.

Marcus Wood’s forte is mission-based coffees. He has worked at Redemption Roasters, a specialty coffee brand that trains prisoners with the aim of reducing reoffending. He’s now head roaster at Old Spike Roastery, whose mission is to train and employ homeless people across the business. He’s also recently set up his own brand, Sanctuary Coffee, to support animal rescue.

Wood is a firm believer in the power of Direct Trade.

“When you buy directly traded coffee, you know exactly how much money goes to the producer,” he says.

“Specialty coffee is driven by quality, so we will reward farmers with a higher price if the coffee tastes good. But, a higher spend on coffee doesn’t equal a better kind of function than Fairtrade. That’s not an accurate way to represent how it works.”

Old Spike Roastery sources tens of thousands of tonnes of coffee from a couple of large plantations in Brazil and Colombia that are able to supply that scale.

But, Wood acknowledges this is fairly unique. Around 80% of the world’s coffee is produced in developing countries by 25 million smallholders, each with less than 10 hectares of land.

So, Old Spike Roastery also sources some of their coffee from traders that connect them with farms that have all sorts of different certifications including Fairtrade, Organic, Rainforest Alliance – or have none and just produce great coffee.

Climpson and Sons operate in a similar way.

“I think there’s more to the story than just a certification, personally,” says Ferris. “Climpson and Sons is 20 years old this year and I think something cool is that over 90% of our coffees come from the same producers every year.”

She adds: “For us, it’s a given that we’re going to source coffees from farms that have social and environmental considerations. It’s cool if they’ve got accreditations associated with them, but that’s more of a tick box for us.”

The issue with brands buying Fairtrade coffee on Non-Fairtrade terms

Fairtrade certified coffee can be bought but without having to pay the Fairtrade premium.

Some brands purchasing coffee in this way feel that they are supporting Fairtrade or organic systems, especially when they are paying higher than the Fairtrade minimum directly to the farmers.

But, Fairtrade’s Deans takes a different view.

“This means brands are benefiting from all of the work we do around standards, training and auditing without supporting the Fairtrade system, or helping the producers to pay for those costs,” she argues.

“We want the farmers to sell their coffee, and we want them to be able to sell 100% on Fairtrade terms, because this is where they will see that full return on investment and benefit most.”

Nick Martell-Bundock is Head of Purpose at Cafédirect, a purpose-led social enterprise that was set up by Oxfam and a number of other NGOs to find an alternative around a coffee crisis in 1991. They buy 100% Fairtrade and 60% organic certified coffee.

“Where’s the capacity building in this model?” he asks of the Direct Trade approach.

“The value of Fairtrade is also in the policy and advocacy work. It’s in the work on their centre of expertise for human rights and environmental due diligence. It’s in the producer-led organisations and the value those organisations have in terms of representing their membership and directing the work more locally to reach the small-scale farmers who need the most support.

“I think to say ‘we pay more’ is a very narrow lens to a much more complicated supply chain and it doesn’t really get fully to where the share of value is.”

How Fairtrade coffee works

When a brand buys on Fairtrade terms they’re committing to two things. One, to pay a minimum price, currently set at $1.40 per pound, no matter how low the market price for coffee falls. If the market price is higher then brands pay the higher price. This payment goes directly to the farmers.

On top of this, brands commit to paying a ‘premium’ of 20 cents per pound which is paid at the co-operative level, with democratically elected representatives deciding how the money is spent. This can be on anything from an organic compost project to supply members with cheap but good, ecological fertiliser; a laboratory to grade the quality of their members coffee; or a maternity clinic to benefit mothers in remote communities who would otherwise have to travel long distances to a hospital.

In 2020, 50% of the premium was spent on services to farmer members, 48% was spent on investments in co-operatives, and 2% of services to communities.

Farmer Maria Paula, a farmer from the Ascarive co-operative in Brazil which supplies Matthew Algie, a Scotland-based coffee roaster, emphasises:

“One very important thing in the production of coffee certified by Fairtrade is the premium because it is with this premium that we are able to develop projects and help and support producers.”

Fairtrade also works with producers via in-country support from Producer Networks, which provide training to farmers to improve the quality of their coffees (which could in turn fetch higher prices for them).

This includes introducing different processes such as natural washes, honey processing and anaerobic fermentation to bring out different flavours.

Training and hands-on support from so-called ‘technicians’ or agronomists can drive up the quality of Fairtrade coffee that is available, and the Producer Networks run competitions to find the best Fairtrade coffees in different origins in Latin America and Africa.

“I got involved in the Fairtrade co-operative for the monetary return. But, as time went by, I realised that it is not the extra money that makes the difference for us, but the teachings and the care for the environment,” says Luiz Brazil, also from the Ascarive co-operative.

“In all the meetings that we have, even today, we exchange ideas with one another. When a technician goes to other farms in other regions, he brings back ideas to share with us. The more we improve, the more our coffee quality improves and production increases.”

A fellow member of the co-operative, Liliane Eliete adds:

“Fairtrade is a way of adding value, not only to our product, but also to our lives. Fairtrade has changed our lives completely.

We have learned a lot and are already teaching our children. My daughters are teenagers and have the opportunity to take many courses and participate in many projects. When I was their age, I didn’t have those opportunities.”

The challenges with buying Fairtrade

But, Fairtrade is not without its challenges.

Fairtrade sales generated over £73 million in Fairtrade premium in 2020.

These premiums are paid directly to the co-ops to invest in the projects they prioritise.

This can create tension with brands whose customers are demanding transparency and who want to report on ‘impact’ for marketing purposes.

The crucial aspect of the Fairtrade premium is farmer empowerment. The farmers get to make the choices for themselves and their communities on how the money they earn is spent. The decision is not made in a boardroom halfway across the world by someone who has less understanding of the needs of communities.

“I’m slightly torn on Fairtrade,” one UK CEO explains.

“As a brand owner I buy into Fairtrade. But, we need to know how the premiums are being spent. We’ve got to be given all the tools to help us explain to our customers what they’re supporting.”

Fairtrade and transparency

I posed the issue of transparency to Cafédirect’s Martell-Bundock.

“I think some of the questions are fair. We should all always be challenging to make sure there’s accountability for where the premiums are going,” he answered.

“I also think, at times, there needs to be some trust in Fairtrade and in the co-operatives who are receiving the premiums and the communities who get to determine where and how they spend the money.”

Transparency for auditing purposes and transparency for marketing purposes are two different things. Fairtrade, and the independent auditors FLOCERT, insist the premium is rigorously monitored.

Deans, Fairtrade’s Supply Chain and Programme Manager, says:

“We have really tight rules in place. For the use of the premium, Fairtrade farms have to have a plan for what to spend the investment on, it must match clear developmental outcomes and everyone has a vote to ensure it reflects the needs of all members, everything is recorded and this information is all audited.”

“Working out a brand’s specific impact can be done, but it is a lot of work and we don’t have the capacity to proactively offer this. Co-operatives might not have the time to work with us on gathering case studies about the impact of Fairtrade premium being spent on a school and why that’s been important for a local community, for example.

“However, there is nothing to stop a business building a direct relationship with a co-operative to find out this kind of information, and if they can invest marketing resources in doing so, even better.”

How Fairtrade and Direct Trade can work together

As Hoffman’s YouTube video implies and Cafédirect’s model proves, the choice doesn’t have to be between Fairtrade and Direct Trade. It is possible to have both.

“I have some pretty strong views on this,” says Danelaw’s Jameson, who has been working in the industry for 17 years. Drawing on his experiences, he says:

“Union Coffee is Direct Trade focused and I like a lot about their approach. Grumpy Mule (owned by Bewley) is Fairtrade-focused and I like many elements of that approach.

But actually, where I feel most happy is somewhere in the middle, working with certified co-ops and being able to talk directly to the producers. It’s more work. And it’s worth putting that work in.”

Having only launched this year, Danelaw is still in the process of certifying as Fairtrade and Organic.

“I believe certification will provide longer-term stability, but there’s things the business needs to keep running day-to-day that feel more urgent,” he explains.

Jameson draws parallels of being a small-business owner with the choices small-holder farmers are faced with every day. He describes a project he worked on in Honduras, with Grumpy Mule.

One of the Fairtrade-certified co-operatives they sourced from is a four-hour drive from the nearest town and the community had an urgent need for an ambulance, which, understandably, is what they wanted to spend their Fairtrade premium on.

However, Grumpy Mule also identified a longer term problem in the area, which was that as a former conflict zone, many of the new generation of farmers hadn’t had the opportunity to go to high school. For coffee farming to continue to be viable over the next 20 years, they needed to invest in training the farmers to learn how to improve yields and quality.

So Grumpy Mule sought external funding, and with the support of Fairtrade, set up a young farmer’s academy to focus on this long-term strategic direction.

Jameson uses this as an example of the best of using a combination of the Fairtrade and Direct Trade models.

But, if a community decides to spend the premium on an ambulance rather than a training academy can we really judge that to be a bad choice? If a brand decides to invest in a training academy to secure their supply chain, and get good PR in the process, is that really a better choice?

Shouldn’t communities be earning enough for both?

So, what’s a good cup of coffee?

Well, it’s complicated.

There are definitely some brands producing some wonderful coffees who are doing excellent work with the coffee farmers they are trading directly with. You can seek these out and ask questions of the brands to make sure you are buying in line with your values.

You can also look for the Fairtrade mark, which offers some key guarantees around sourcing, without you having to do additional research.

These are all worth supporting.

It’s also worth knowing what coffee brands to avoid.

Many more coffee farmers are still being exploited by the industry giants. Just a handful of corporations control the majority of the roasting and marketing of coffee and despite their supposed sustainability efforts, the status quo isn’t changing.

“The asymmetries in power and information among participants in the global coffee market result in some stakeholders benefiting more than others; especially the coffee roasters appear as the big winners,” reveals the 2020 Coffee Barometer report.

It concludes: “The coffee sector’s extractive model of production – relying on rural poverty, devalorised work and the depletion of natural resources – denies that a price has to be paid for labour and land use at origin.”

So, it matters where you buy your coffee from and the work that brand is doing to support the farmers. And it matters how they’re investing in further advocacy to help change the system.

Main image: Fahmi Fakhrudin on Unsplash