The best sustainable men’s activewear for the gym, hiking, swimming and more…

This year marks 10 years of Fashion Revolution, the fashion activism movement borne in the wake of the Rana Plaza disaster in 2013, in which 1,134 people were killed and more than 2,500 injured when a clothing factory collapsed in Bangladesh.

It’s estimated that the $1.3 trillion clothing industry employs more than 300 million people globally. Many of them are women. Too many are exploited by fashion brands. Meanwhile, fashion advertising suggests they are allies in women’s empowerment.

In the wake of the #MeToo movement, and learning from decades of experience fighting for women’s rights, women-led unions from across Asia are joining forces with one goal – to end violence against women in garment factories.

And they are starting to see success.

Their ground-breaking research reports have exposed gender-based violence in factories working for international brands H&M, GAP and Walmart – among others.

At the height of COVID, their cooperation was fundamental to exposing the brands who cancelled orders and withheld payments, leading to a global campaign that pressured many brands to #PayUp.

Two years ago, H&M signed a landmark agreement to eradicate discrimination at one of its largest Indian suppliers. It is the first time a brand has ever signed an initiative to tackle gender-based violence in Asia’s garment industry. Although, it came at a high price. It is the result of a year-long #JusticeForJeyasre campaign by unions, following the murder and alleged rape of Jeyasre Kathiravel, a young Dalit woman who worked nights at the factory so she could attend university, by her supervisor, in January last year.

So, how much progress has been made since then?

We speak with five union leaders from India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Cambodia, who are working together to ensure meaningful action is taken when it comes to fighting for women garment workers’ rights. They share the empowering stories of their struggles and successes – and what inspires them to keep going, against all odds:

Lalitha Dedduwakumar, Sri Lanka

Member of the Women’s Leadership Committee of Asia Floor Wage Alliance and Chief Organizer and founding member of Textile Garment and Clothing Workers Union. Also Co-Chairperson of the Women Led Bargaining Committee

“There’s a structural violence against women that has become normalised in society, and it has become normalised inside the factories, as well.”

“I started working in a garment factory in my village when I was 28, because my family was poor. Three years later, the factory closed down without warning. I felt the injustice. But, I had no knowledge of workers’ rights, unions, brands or any of the things that we talk about now.

There were about 500 workers in the factory and we joined together to fight the closure. Our family was lucky, we could still afford food, but we spent all our savings pursuing justice.

We marched eight kilometres, from the factory to the labour department offices in protest. Unions offered their support and our case was taken to the High Court. It has been 15 years and the case is still ongoing. Across the industry, injustice continues.

During COVID, apparel sector workers were declared essential workers. At the same time, all workers in Sri Lanka suffered temporary pay cuts of 50 per cent. This meant some people couldn’t afford to get to work. The government awarded state sector workers a 5,000 Rupee (£12) pay rise, which increased monthly wages by about 10-15%, but garment workers weren’t entitled to this.

There are several reasons for this discrimination. The first is that the vast majority of garment workers are women. There’s a structural violence against women that has become normalised in society and it has become normalised inside the factories as well. It’s not unheard of for women to be nicknamed after the machines they work on – for example, “Juki Kalla” (‘Juki’ is the sewing machine brand and ‘Kalla’ is a derogatory way of saying ‘a girl’) or “Juki Baduwa” (‘Baduwa’ implies someone is a prostitute and is also a way of slut-shaming) – rather than by their names.

There’s also racism. There’s been an increase in migrant workers, who don’t necessarily speak Sinhala. They are treated as second-class citizens and denied access to government assistance.

Underpinning all of this is the class issue. Even working in trade unions, as a working-class woman I have experienced discrimination and purposely been kept out of certain policymaking processes. That’s why we founded a trade union led by female ex-apparel sector workers.

Since COVID, things have got worse. There has been an economic crisis that means real wages have collapsed by 40% and factories are either closing down, merging or reducing working hours because garment sector exports have declined due to the global recession. Those that continue to exist are faced with increasing production costs because of energy bills, fuel prices and utility bills.

This all means women are faced with job losses and wage losses. At the same time energy bills and utility bills in the home have significantly increased putting pressure on workers’ incomes. Increasingly workers are getting into debt and forced into migration without proper protections.

Plus, factories are putting more pressure on workers to work longer hours for lower wages. They do this in two main ways. The first is increasing targets and putting pressure on workers to deliver more during the 8-hour workday. This leads to increases in gender-based violence and harassment incidents. The second way is to force workers into illegal overtime and not paying the legally entitled allowances. Again, women workers increasingly face harassment, verbal abuse and income losses.

We want to work, we don’t want the factories to leave. But, we want to work with dignity.

This is increasingly hard. Especially as the government is also trying to remove labour protections for workers through the new labour law reforms. This will be especially bad for women workers with further relaxations of laws on termination, wages and stricter laws on freedom of association.

It takes a lot of courage for women to join and to stand up for themselves and each other. They risk their job, intimidation, and discrimination from employers. It’s especially difficult for women who are used to being controlled to show leadership.

What’s incredible is that when a woman becomes used to working in a safe environment and is treated with dignity and respect, it changes her expectations of how she is treated in her home and community, too. It’s completely transformative.

There’s a good chance we have produced some of the clothes you wear. We want you to understand the plight of the workers who have made these. We need your support in demanding change. Please look out for calls for your governments to hold clothing brands to stricter regulations. Please don’t look away from our calls for living wages and workplaces free of gender-based violence and harassment.”

Dian Septi Trisnanti, Indonesia

Founder of Inter Factory Labour Union/FBLP (2009 – 2021) and Federation of Indonesian United Trade Unions/FSBPI (2021); Director of the documentary Angka Jadi Suara (Numbers Become Voices) that captures gender-based violence experienced by women workers in their daily lives; Author of The stories of pregnant workers during the pandemic (2021) and Women’s Silent Song.

“I want women around the world to know the story behind their clothes, the story of exploitation.”

“Helping other women is healing for me. We are oppressed, yet we stand in solidarity with each other. We face hardship, yet we share our kindness.

That’s what inspires me to keep going when I’m being arrested and beaten by police officers for protesting. It empowers me to continue to speak out when the board members or bosses I’m negotiating with speak to me or touch me inappropriately, even though the common response is: ‘Maybe he was just trying to be nice’.

I started out as a journalist and soon realised it doesn’t matter what industry you’re in – wherever we work, women face similar oppression.

I find working in the garment industry a lot of pressure and it can be hard to handle. We receive a lot of cases detailing women’s abuse, including sexual harassment and rape. It’s so common we still have to put up signs in factories that say: “This is a sexual harassment free zone”.

Despite their low wages, female garment workers are often the breadwinners but our culture refuses to recognise that. Women, so used to being reduced, don’t see it in themselves, either. The fact is, brands from the west exploit this gender imbalance.

During COVID, there were a lot of policies that disadvantaged workers including ‘no work no pay’ policies and wage cuts of up to 25%. This put a lot of pressure on women to work whenever it was available. One woman was sick with COVID and still came to work. She was afraid her boss would cut her contract if she didn’t. Instead, he yelled at her for not hitting her target, she fainted, was taken to hospital and died.

At the height of the pandemic, factories operated a shift system so that only fifty per cent of workers worked at one time. The first shift started at 6am, and the workers would have to wake up in the middle of the night to do all the housework and arrive for 5.30am. Many did not have breakfast. Can you imagine how exhausting it was for them?

There was added pressure because the shifts were six hours each instead of eight, so women had to work weekends to make up the hours.

Now, workers are still losing jobs and become poorer. They are not consulted politically, with new job laws being processed without workers’ participation. The economic crisis is putting further strain on families and the stressful double burden on working mothers – to put food on the table and ensure their children are doing well at school – is creating high tension in their relationships. Therefore, mentally and physically, many women workers are not in good health.

I want women around the world to know these stories behind their clothes – the story of exploitation. I want them to know so they stand in solidarity and help the voices of women garment workers to be heard.”

Rukmini Vaderapura Puttaswamy, India

President of Garment Labor Union (GLU) based in Bengaluru, Karnataka state and member of the Women’s Leadership Committee of Asia Floor Wage Alliance

“Brands are the biggest game players”

“I worked as a tailor in garment factories for 23 years. I saw all kinds of sexual harassment, verbal abuse, impossible targets, and a lack of benefits. I became a target when I joined a union and started speaking out for others. The managers tried to publicly humiliate me by criticising my work. They wouldn’t grant my holiday requests. They even followed me to the toilet.

When I became general secretary of the Union in 2006, they realised their tactics weren’t working, so they made false allegations that I was lending money with high interest to co-workers, so they could dismiss me. Initially, they tried to coax colleagues into being witnesses, but they failed to do this and couldn’t prove their alleged charges.

I was able to fight back because of support from the union, who got a brand involved. To this day I am paid a salary even though I no longer work at the factory.

But, brands don’t typically support unions. They are the biggest game players. They sign ‘codes of conduct’ with the factories that say workers should be entitled to unionise when behind the scenes they refuse to give factories any more orders if a union is recognised.

Both the factory managers and brands together keep unions from working with factories. Workers who enrol in unions are punished and union busting (activities undertaken to disrupt or weaken the power of trade unions) is commonplace. Plus, despite increased due diligence laws in parts of Europe, brands are still refusing to enter into enforceable agreements with unions to support workers.

It’s clear brands only respond to crises when they have to – this is why putting global pressure on them to protect workers is so important.

The majority of garment workers don’t have much education or any awareness of their rights. They’re women who go from being controlled by men at home to being controlled by men at work. Brands and factories exploit this by paying them very low wages, threatening salary cuts for absence, and refusing to give them long-term contracts so they remain vulnerable.

In my experience, we’re still a long way from a ‘good’ factory. The best are the ones that are willing to address issues when a union confronts them. Without a union, factories can fire workers without notice. When a union is present they are more likely to follow legal procedures and give workers benefits, such as leave.

Women are more powerful when we work collectively. That’s why we need unions, and for unions to work together.”

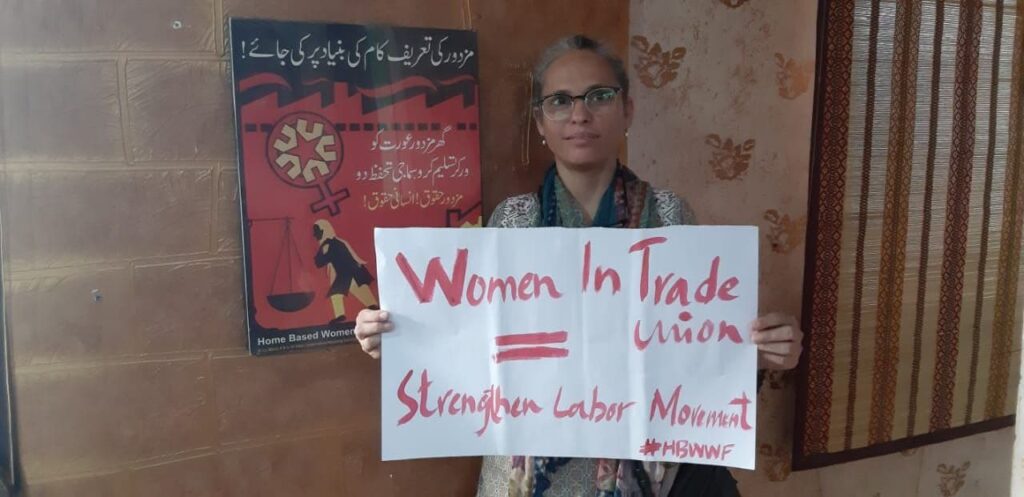

Zehra Khan, Pakistan

Founding member and General Secretary, Home Based Women Workers Federation (HBWWF) and member of many tripartite committees, including the Sindh Home Based Workers Governing Body.

“We realised women didn’t just need help starting a business. We needed to make them visible in the eyes of the law.”

Interview from 2022: “Change is coming. Not just in the workplace, but also in the home. One woman told me her husband no longer hits her because she’s not isolated anymore, she now has 3000 union members standing behind her!

It’s a common story. Domestic abuse declines when men consider their wives to be more equal partners in earning money and running the household. Husbands and fathers realise the benefits of educating women, rather than fear it. Men are now joining our union too, and even those who are not members are coming to us for advice and legal support.

Our union is the first one created for Pakistan’s so-called “invisible workers” – the home-based workers, which we estimate account for about 12 million women in Pakistan. [1]

The informal sector dominates the Pakistani economy. We estimate it now accounts for up to 80% of total work because the majority of the workers are hired under an uncertain third-party contract system. Home-based workers are not officially recognised. In fact, many don’t consider themselves to be workers at all, because they cut and sew from their homes. Yet, they typically work 12 – 14 hour days. They use their own electricity and gas. They receive very low wages, sometimes paid in other currencies, and often their daughters assist with the work for no payment at all.

When we founded the Home Based Women Workers Federation in 2009, our initial goal was to create a cooperative where women could support each other and negotiate collectively, to give them more power. Then, we realised they didn’t just need help starting a business. We needed to make home-based workers visible in the eyes of the law so they would be entitled to receive a minimum wage and gain access to health and pension schemes.

So, we pivoted our focus. Following almost a decade of protesting in the streets and meetings with legislators, the first legislation that recognised the rights of home-based workers was passed, in 2018 [2].

It’s been transformative. Our members negotiate better prices and refuse very low paid work.

They are also becoming more confident. In the early days, we had to persuade women of their rights and they were afraid to take part in protests. Now, they ask when the next demonstrations are and they chant slogans in the streets. Members are part of ‘tripartite committees’, for example the Sindh Minimum Wage Board, that are set up so unions, employers and governments can officially negotiate on contentious issues. They also use their experience to support other movements, from helping formal workers to unionise to assisting with indigenous people’s land rights issues.”

References:

[1] https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/753706-home-based-workers

[2] https://tribune.com.pk/story/1706333/sindhs-home-based-workers-protected-new-law

Heng Chenda, Cambodia

Vice President, Cambodia Labor Confederation (CLC), Chair of CLC Gender Committee and General secretariat of Coalition of Cambodian Apparel Workers Democratic Union (CCAWDU)

“I knew in my heart to demand for more.”

As a garment worker, I witnessed lots of violence and injustice. At the time, I didn’t understand the law, but I knew in my heart to demand for more. I knew I needed to protect myself and my female colleagues.

Female workers are facing violence, harassment, prosecution, and threats. Plus, most workers owe money to the bank due to the lack of jobs and economic crisis.

It’s not easy because these problems stem from societal issues, where women aren’t considered equal to men. Added to this is the fact that politically and economically Cambodia is not very stable. Plus, the laws don’t work in favour of workers. Factory owners bribe police and hire gangsters to intimidate us – I’ve been pushed in front of cars while protesting. But, if we don’t challenge this now, future generations will face the same violations.

Our goal is for all girls and women to understand their rights and be able to stand up for themselves. We do this by working to increase the amount of female managers in factories and female leaders in unions – and to ensure their leadership is respected. At the same time, we campaign for labour laws that give women maternity rights and criminalise gender-based violence.