In collaboration with Brothers We Stand

When it comes to sustainable fashion, transparency is key. But, what does transparency really mean? And how much does it tell you about the ethics or sustainability of a brand?

The argument for transparency is, when fashion brands publicly share details of their supply chain, from where they source materials to how these are sewn together and by who, it means they can be held accountable for how their garments are made. If there are environmental problems or human rights abuses – violence, child exploitation and slavery are prevalent in the fashion industry – these can be more quickly identified and dealt with.

Transparency is so important that following the Rana Plaza factory collapse on 24 April 2013, which killed 1,138 garment workers, the global charity Fashion Revolution was founded. Every year, it publishes its ‘Fashion Transparency Index’. The Fashion Transparency Index ranks 250 of the world’s largest fashion brands and retailers according to how transparent they are. This means, how much information they reveal about their supply chains, social and environmental policies, practices and impacts.

The Fashion Transparency Index: How transparent are fashion brands?

Last year, The Fashion Transparency Index revealed that brands are not really very transparent, at all. Only 2 out of 250 brands disclose data on the number of workers in the supply chain who are actually paid living wages. Only 12% of brands publish their actions on the promotion of racial equality. Crucial environmental data is not reported, for example, 95% of brands do not disclose their annual water footprint at raw material level…

So, although transparency is a buzzword many brands talk about, there’s still a long way to go for genuine openness and honesty in the fashion industry.

What does genuine transparency look like in the fashion industry?

One fashion marketplace that is leading the way on transparency is Brothers We Stand. Founded in 2013, Brothers We Stand is now one of the UK’s biggest online platforms for sustainable menswear.

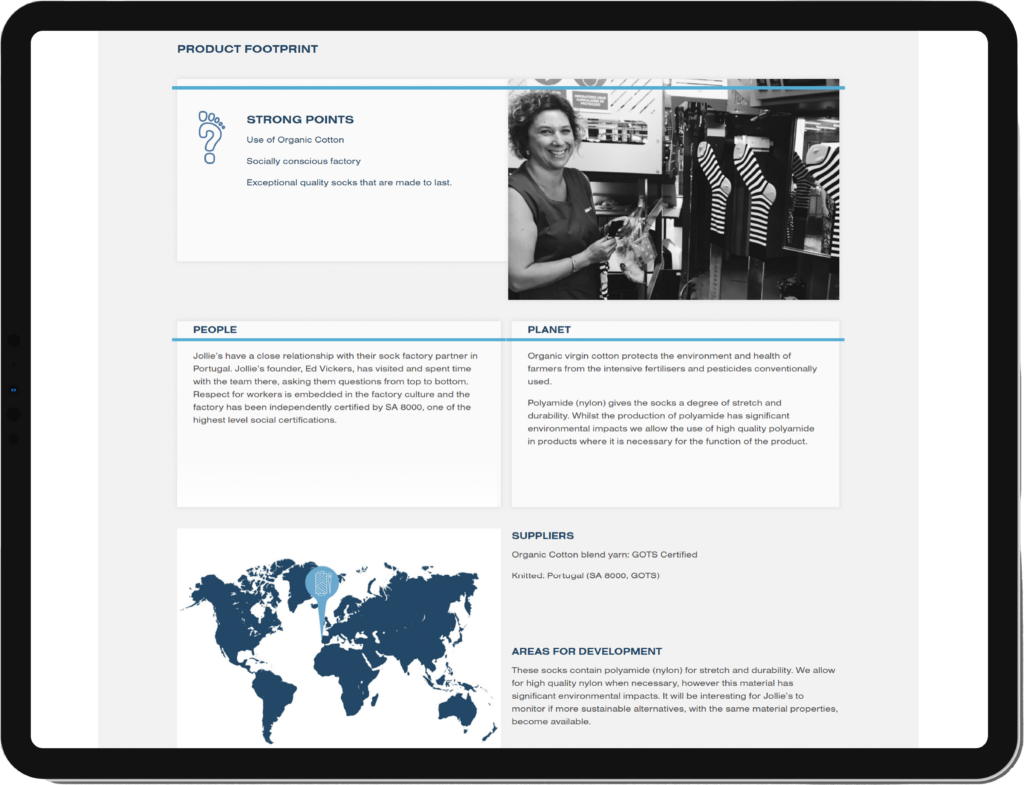

Their commitment to sustainability and transparency is particularly impressive in three ways. The first, they only feature sustainable brands and have a six-point standard for deciding who makes the cut. The second is that they then assess each product from each brand independently before adding it to their shop. They don’t assume that just because they like the brand, all products fit with their ethics. Most unusually of all, for every product they write a full ‘product footprint’, detailing the product’s impact on people, the planet and, crucially, areas where the brand could improve.

So, we sat down with Brothers We Stand marketing manager, James Venvell, to discuss transparency in more detail. We asked why it’s important to tell the whole story? What information to look for when buying from a brand? And how do we avoid brands who are using transparency to pretend they are more ethical and sustainable than they really are?

Let’s start with, why transparency?

Fast-fashion brands have pummelled customers with advertising over the past 30 years. Their messaging encourages people to buy more and more, without consideration of the people and planet that produce our clothes.

At Brothers We Stand, we want to help our customers go from being passive consumers to active agents of change.

That means moving away from having misleading information pushed on them, to understanding where their clothes are coming from, and what impact their purchase will have.

Essentially, our goal is to give them all the information, so they can make their own, more informed, decisions.

What impact does transparency have?

Transparency is a powerful tool in protecting workers and the environment. Where consumers are demanding transparency, it’s a lot harder for brands to get away with cutting corners and to cover up bad behaviour.

One example is the #PayUp social media campaign which challenged brands to honour contracts with factories during the pandemic. Thanks to the exposure and awareness this movement created, brands were held accountable for not paying their workers and many paid. Many more are still being pressured to pay.

What are the limitations of transparency?

While transparency is a powerful concept, ensuring a brand is truly transparent is far easier said than done.

As with all the concepts in sustainable fashion, it can fall victim to greenwashing.

Brands can paint a pretty picture of a factory worker on a website alongside a nice story to convince customers there’s a good supply-chain – even if there’s not. It’s very loosely regulated, so brands get away with this all the time.

You have an ‘areas for development’ section where you clearly state what improvements brands and products can make. We love it. Tell us more.

Sustainability is a journey, and not an easy one! There are many different ways of being sustainable. So as long as a brand is showing a commitment to sustainable development, we want to support them in that.

Nevertheless, customers deserve to know if there are any cracks in a brand’s supply chain. At Brothers We Stand we want to give them the whole picture, not just part of it. We also want to acknowledge that not every brand is able to solve every issue.

This encourages brands to be better and they tend to respond really well to it.

For example, for many of the brands selling on Brothers We Stand we are one of the only marketplaces they have chosen to sell on. They want to work with us because they believe we’re serious about what we’re doing and they appreciate that we are always looking for how we can go one step further.

If there isn’t a genuine commitment to ongoing development, brands could make nice profits selling a few organic cotton t-shirts with good marketing spiel. But, that doesn’t change anything.

So, how can customers tell when a brand is being genuinely transparent and not just using transparency to greenwash?

It’s difficult. Until recently, a brand could claim their piece of clothing is sustainable without backing the claim up. Fortunately, the government has taken action to start weeding out the greenwashers. But, this will take time, so you may still encounter false claims.

For these, checking whether a brand has third party certifications – like GOTS, SA8000, Fairwear, or Soil Association – is a good place to start. These certifications show that someone else is checking that a brand’s claims are true and that they are being held accountable for that.

Also, checking if brands are featured on sites like Live Frankly or shopping on sites like Brother’s We Stand provides an extra level of assurance. We want customers to come to Brothers We Stand knowing that it’s a place where they can make safe buying decisions, and not have to worry about what underlying impacts there might be. We’ve done that work for them.

If I’m buying directly from a website, I always go straight to the ‘about’ page or ‘sustainability’ page. Generally, the more in-depth and specific the information they share with you is, the safer it will be. If they’re just relying on generic terms, like ‘ethical’ and ‘sustainable’ and not actually telling you how, then that’s a bit concerning.

As a rule of thumb the more research you do, the less likely you’ll fall prey to greenwashing or get caught out because you’re backing yourself.

But, that’s a hugely unfair demand to put on consumers, and this is the problem we want to solve at Brothers We Stand.

What’s the one thing you wish consumers understood about fashion and sustainability?

One thing that I would say is that the cost of sustainable fashion is worth it. We understand that now more than ever, living costs are going up and it can be difficult to spend that extra bit on clothes, especially when we have the option to spend so little with fast fashion.

But, I’m a firm believer that spending less now will cost us more in the future. Because our decisions as consumers are propping up businesses that aren’t good for us, for workers, or the environment and have longer-term impacts.

It costs more for Idioma to use Fair Wear Foundation factories that look after workers. It costs more for MUD Jeans to use laser technology over chemicals to produce the worn out denim effect. And, for brands like Yarmouth, Brava and Knowledge Cotton Apparel, you can literally feel the higher quality of material between your fingers. That costs more, too. But, its durability lowers your footprint, and locks in your style for longer.

More than 100 billion pieces of clothing are said to be produced each year. Does where we buy our clothes from really make a difference?

Absolutely. It may seem like a small decision, but that choice matters.

It matters to every single person who had a hand in making that item.

When you take a purchase away from a brand like H&M and give it to a brand like Knowledge Cotton Apparel, you’re sending a message that you’re not interested in the way H&M are doing things anymore – and brands pay attention to that.

If everyone changed their purchasing habits, then it would be billions of people voting for a different kind of industry.

What’s exciting you in sustainable menswear at the moment?

Sustainable menswear has definitely been slower to grow than womenswear. But, we’re at an exciting stage.

We’re now seeing the range of ethical menswear expand. There is your classic adventurewear which Level Collective and Silverstick are great for, and your timeless classics that Knowledge Cotton Apparel sell. We’re also seeing brands like Brava Fabrics introduce more colours, styles, silhouettes.

Plus, there’s a far broader range of materials being introduced, like hemp and EcoVero™, and truly circular designs from brands like MUD Jeans.

Shop sustainable menswear brands at Brothers We Stand.

Brothers We Stand is one of the UK’s biggest online platforms for sustainable menswear. They are leading the way in fashion transparency and every product includes a full ‘ethical footprint’, detailing the product’s impact on people, the planet and, crucially, areas where the brand could improve.

Main image: The Brothers We Stand team: (from top to bottom) Jessica Sprouse, Jonathan Mitchell and James Venvell.