The best BBQ Delivery Boxes in the UK from small sustainable British Farms

Written in collaboration with Moshi Moshi and Sole of Discretion, as part of our sustainable seafood event.

Is there such a thing as sustainable fish?

Absolutely.

That’s not the question we should be asking, though.

The real question is, how long will there be any seafood if we continue to fish the way we are?

“We see that fish stocks are collapsing. Most of them have collapsed. We’re now fishing on the West Coast [of Scotland] for the bottom of the food chain, that’s all that is left,” says Danny Renton, founder of Seawilding, in The Custodians.

It’s a similar story across the UK, Europe and the world.

Large fish populations have decreased 94% due to bottom trawling over the last century [1].

And we’re not giving them a chance to recover.

This is having devastating consequences on our oceans (no fish means no fish – not for us, not whales or dolphins or polar bears…), our coastal communities (lack of jobs and incomes…) and for our futures (seagrass captures carbon up to 35 times faster than tropical rainforests [2]).

“About 70% of the planet is the sea, it’s vital for all ecosystems – and yet we treat it like a trash pit,” sums up Renton.

Here’s the headlines for the biggest issues when it comes to fishing and seafood…

Sustainable labels: MSC Blue Tick, Dolphin friendly etc

In 2020, global capture fisheries production was a staggering 90.3 million tonnes [3].

Aquaculture production (fish farms) produced a further 87.5 million tonnes of animals for food [3].

Yet, the FAO also reports that around a third of all fish, crustaceans and molluscs harvested from oceans, lakes and fish farms are wasted or lost before they ever reach a plate [4].

A reported 92% of the 230,000 tons of fish discarded in Europe comes from bottom trawling — and that’s just what’s recorded. The real figure is thought to be much higher [5].

So, how do you know when you’re buying genuinely sustainable seafood?

Do you look for the MSC blue tick? Do the words ‘dolphin-friendly‘, ‘gastro’ or ‘finest’ or ‘wild’ make you feel better about what you’re putting on your plate?

What if we told you that it’s highly unlikely these mean what you expect them to?

Mainly that none of these terms mean ‘sustainable’.

Not even the MSC-certified blue-tick label, which the WWF (who helped to set MSC up in 1996) have now publicly expressed their concerns about [6].

The MSC certifies around 50% of UK landings [7] and 20% of global catch [8], accounting for more than 10 million tonnes of fish a year [7].

Industrial fishing operations now cover more than 55 percent of the ocean surface [9]. They also use hugely destructive fishing practices like trawling, long lines, gillnets and dredging.

It’s on the MSC’s watch that fish stocks are plummeting and the ocean floor is being decimated.

All the while telling us to ‘look for the blue tick’.

What’s in it for them, you ask?

Well, the MSC’s income last year was £29.8 million – almost 90% of which comes from the licensing fees it charges businesses for the right to use its label [10].

They are literally paid to certify destructive fishing practices – and, arguably, promote them as sustainable.

Overfished vs underfished species

Before reading on, take a moment to list all the different types of fish you eat. What number do you reach?

Is it anywhere close to 100?

“Around 150 different species of fish are caught off the UK coast. But, around 80% of the seafood we eat in the UK comes from only five different species – Cod, Haddock, Tuna, Salmon and Prawns,” explains sustainable seafood advocate, and founder of Moshi Moshi and Sole of Discretion, Caroline Bennett.

“I think to some extent these species are the most commonly eaten simply because they are what’s presented to consumers. That’s what we’re familiar with.”

So, would we like other types of white fish, if we tried them – Plaice, Pouting, Gurnard, instead of Cod and Haddock?

“Our Sole of Discretion customers are definitely liking them!” exclaims Bennett.

“If you give somebody a Whiting or a Pouting and ask them if they would pay twice this or three times this price for Cod or a Haddock, most say: ‘Oh no. This is great!’. Others can’t taste the difference. It is indistinguishable, particularly if it’s been cooked in a batter or a breadcrumb.”

One of the reasons industrial fishing systems have focussed on Cod is that it has a longer shelf life. Plus, it’s bigger than other white fish so it can be easily processed and frozen on board, which is important for boats that are out for days or weeks at a time. On a successful fishing expedition a big, industrial boat can land around 100 tonnes of the same species.

Whereas smaller boats, which are typically under 10m, land anything from as little as 100kg up to around 2 tonnes in one trip, and land a variety of species of all different shapes and sizes that have to be processed individually.

“This variation doesn’t lend itself so well to a mass produced market,” says Bennett with a mix of frustration and resignation, which is why she set up fish-box delivery scheme Sole of Discretion.

“They work perfectly well in Europe though, so are shipped to Spain where you’ll find them on local menus there. Imagine! You’re going to Spain to eat fish from the UK.”

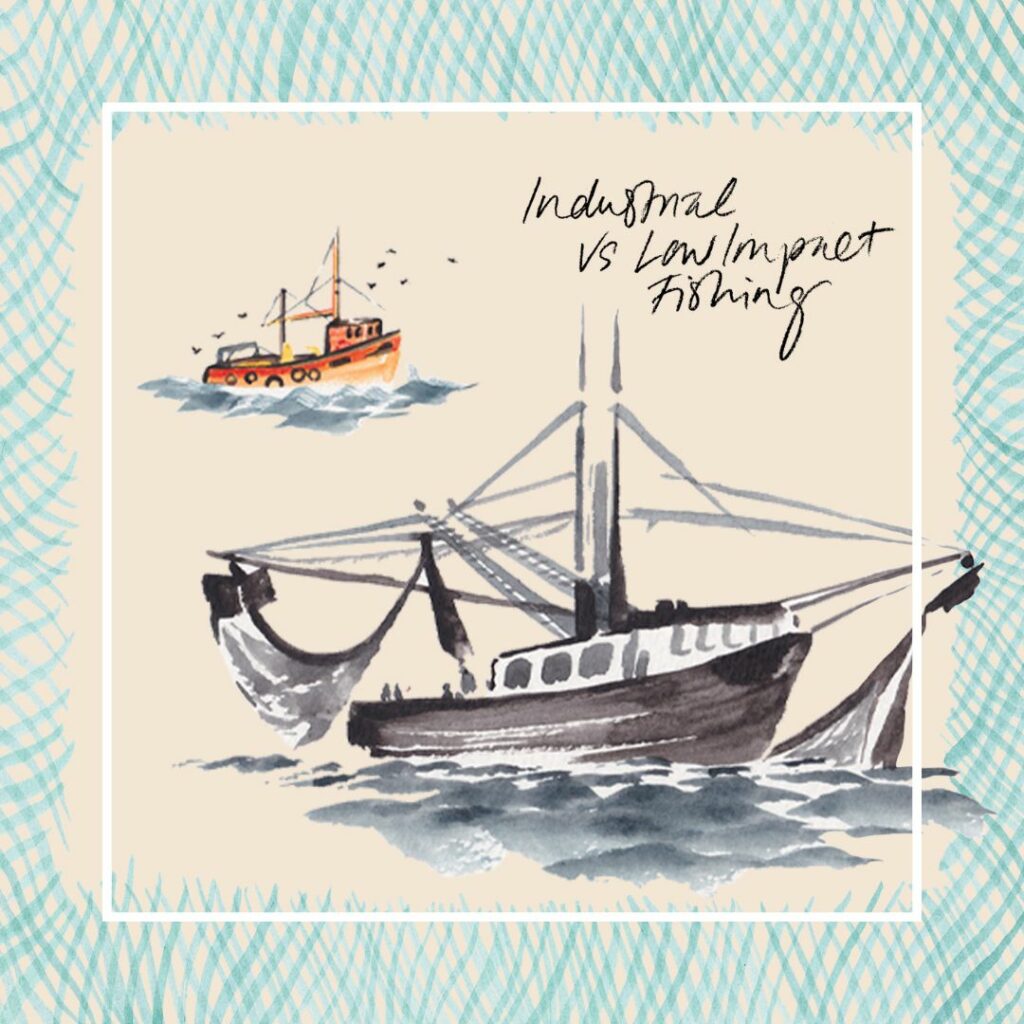

Wild fish and the race to the bottom: Industrial Fishing vs Dayboats

Fishing boats are typically classified into two types:

- Under 10m: known as ‘dayboats’, because they go out to sea and back each day

- Over 10m: Industrial fishing vessels that can be out to sea for weeks. The biggest boats can be up to 1.5 times longer than a football pitch.

“In terms of access to fishing opportunities [quota], the under ten fleet has less than 2% with the large scale sector taking the remaining 98%+ share,” reports Jeremy Percy from the The New Under Ten Fishermen’s Association, the only dedicated representative body for the under ten metre fleet in the UK.

The difference in methods of catch are huge. The small boats tend to use nets and creels and fish by hand, treading lightly on the ocean’s ecosystem.

The industrial fishing boats are highly mechanised and use equipment like trawlers and dredgers, which scrape along the seabed destroying everything in their path. This includes seagrass meadows, which are as beautiful and diverse as they sound and support biodiversity by providing essential nursery habitat for important fish species.

Bottom trawling happens globally, but European waters are the most trawled. A reported 50% of EU waters are regularly impacted, compared to a global average of 14% [11].

In the UK alone, we have lost up to 92% of our seagrass meadows over the past 100 years [12]. Global estimates suggest we lose an area of seagrass equivalent to two football pitches every hour.

It’s a catastrophic loss. But species and habitats can recover – if allowed to do so.

Trawling and Dredging used to be restricted inshore in Scottish waters. Relaxed laws in 1984 changed that and have changed the ocean beyond all recognition, further destroying the sea floor, fish stocks and local fishing communties.

Prawn trawling is considered the second most damaging UK marine fishery after scallop dredging, according to Open Seas [13], a charity that focuses on data and evidence to call for long term protection of the marine environment.

As such, they have reams of evidence about how intensive trawling simplifies the ecosystem, killing diversity and abundance of marine life.

“Do you know what the really awful part about this is?” asks Bennett.

“An argument industrial fishing boats use now is that they are just dredging the sandy bottom of the sea, they’re not really doing the marine environment any harm. And to some extent, it’s true. But, once upon a time the seabed would have been alive with coral and seagrass meadows and all sorts of fish and now they’ve completely trashed it.”

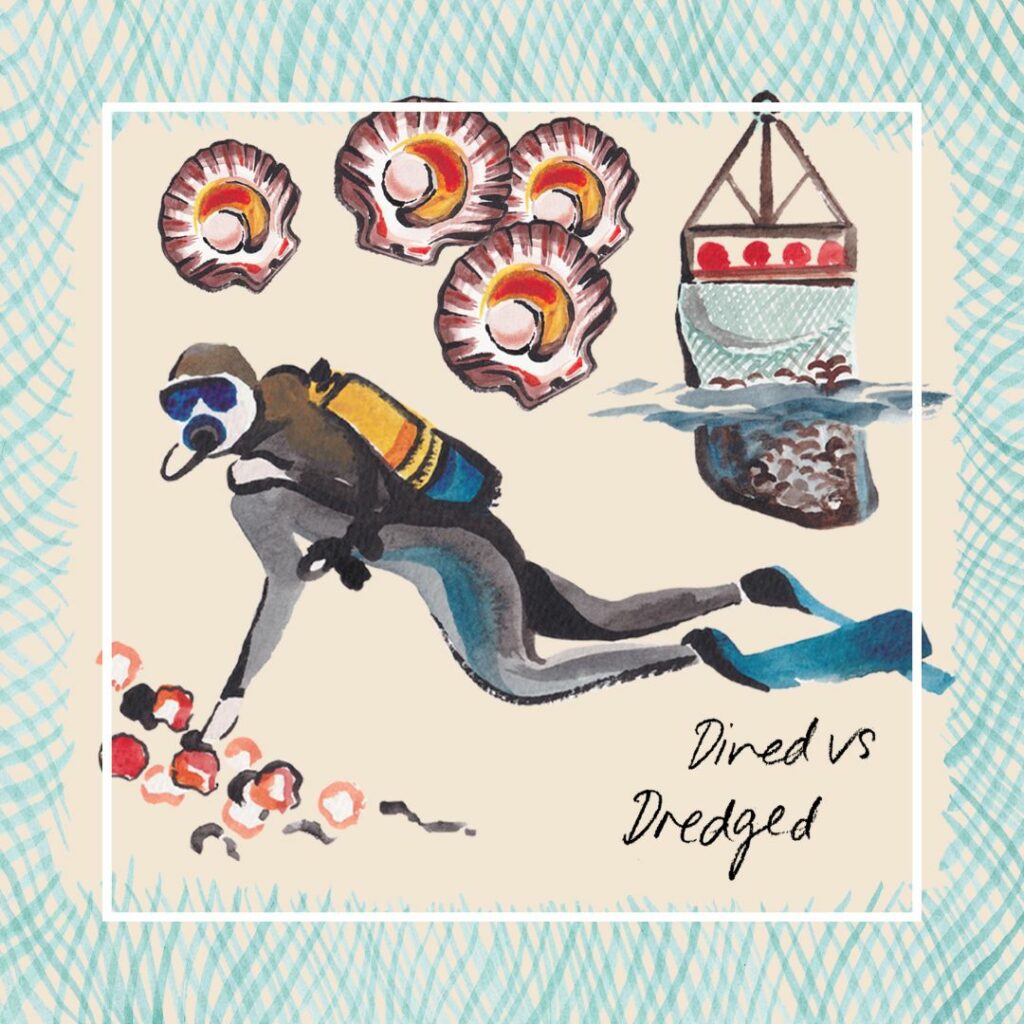

Hand Dived vs Dredged Scallops

There’s still plenty of scallops to be found on the seabed, though. For now. So, gobble them up while you can!

Not really.

If you’re in a restaurant, or cooking at home and scallops are on the menu, the most important question you can ask is: ‘Are they hand-dived or dredged?’

The difference is colossal.

Hand-dived scallops are exactly as they sound, a diver uses their hands to collect scallops from the seabed, discerningly picking the best ones and leaving the young ones to grow plumper.

Dredged scallops are as described in the section above.

“Not always, but often, you can taste the difference because a dredged scallop will be a bit gritty,” advises Bennett.

The difference in environmental impact between the two fishing styles cannot be overemphasised. Yes, hand-dived scallops are expensive, but not prohibitively so.

“There’s just no excuse for serving dredged scallops as a treat,” she insists.

Farmed and Ranched fish

So, what about farmed fish – surely that’s better?

Well…

It’s no surprise that most of the Salmon on the market is now farmed (read our in-depth article about Salmon farming here). But, did you know other species increasingly are, too – including Turbot, Bream, Bass, Trout?

“Tuna and Eels though, are badass,” says Bennett.

This is because they refuse to breed in captivity and therefore can’t be farmed.

Obviously, humans are a clever (and greedy?) species and have found a way around this, reveals Bennett. Tuna is now ranched in Asia. Eels are ranched mostly in China and sometimes Japan.

“Ranching is really bad because they take the fish from the wild and fatten them up,” she explains, adding: “These are the fish that are likely to end up on your plate in a sushi restaurant in the UK.”

So, we take fish from the sea to “farm” it.

And do you know what it’s fed?

More fish taken from the sea.

Farmed and Ranched fish are fed wild fish – 90% of which is considered good enough quality for human consumption [14].

“There are plenty of examples of European boats buying the fishing rights to fish off the fertile North African coast, leaving the locals in Mauritania, Senegal and Morocco no longer able to fish in their own waters,” explains Bennett.

“This could very feasibly be a contributing factor to some of the economic migration from these countries. When young people are unable to earn a living in their own fishing communities they are forced to look further afield for work and potentially risk their lives for the chance of a better future in the West.”

Other issues with farmed fish include the increasing levels of antibiotics required to fight disease in fish farms (lice are a huge issue – yum!). Also, there’s the farm’s carbon footprint for everything from incubating eggs, to raising young fish (fry), to operating mechanised pens…

“The crazy thing is, we don’t need to farm fish. Nature grows plenty and just gives it to us all by itself if we let it do its thing,” emphasises Bennett.

“Full Life Cycle analysis needs to be done, but my hunch is that you can’t get any method of farming – animal or crop – that’s less impactful than catching fish from a small boat.

“We don’t have to be so destructive – we’re choosing to be.”

Human Rights Abuses and Modern Slavery

It’s not just the ocean and fish that are being destroyed by industrial fishing. It’s human lives, too.

Globally, prawn farms are renowned for human rights abuses including violence, intimidation, child-labour, forced and bonded labour. Even murders have been linked to prawn farming in 11 countries, reports the Environmental Justice Foundation [15].

Modern day slavery is a huge problem on industrial boats, too – even in the UK. This is enabled by a loophole in UK law. If boat owners prohibit the crew from coming ashore then they are not subject to British employment law.

“Twenty years ago, the UK fishing industry mostly employed local fishers from the UK and nearby European Economic Area (EEA) countries. There was a well-established ‘hard work, fair rewards’ culture with pay relating to the size of the catch, reports ITF Global [16].

“Now, the sector survives by routinely underpaying migrant fishers. Migrants don’t get paid according to the ‘share of catch’ system. They’re not even being paid the UK minimum wage.

As such, inadequate working conditions, human rights abuses, forced labour, human trafficking and modern slavery, physical and verbal abuse are all rife [16].

And just off our coastline.

If we continue to connect the dots, it’s clear how this is also directly related to the decimation of coastal neighbourhoods, where small boat fishing was once a thriving industry, spreading the wealth and creating many jobs and incomes that were spent in the local shops and pubs creating vibrant communities.

Concentration of wealth

This brings us to our final issue – concentration of wealth.

Industrial fishing companies aren’t just swallowing up all the fish, they’re swallowing up all of the local fishing opportunities too.

A massive 75% of the total quantity of fish caught by UK vessels in 2021 was landed by vessels over 24 metres in length. In 2021, these vessels constituted just 4% of the UK fleet by number [17].

Vessels under 10 metres make up 79% of the UK fleet but only contribute 8% to the fleet’s total capacity [17].

“In Brixham, 80% of all quota is landed by one family. The other 20% is spread across maybe 1000 different boats,” says Bennett.

Last year, Brixham harbour applied for a scheme to double its size and provide more room for “industrial” trawlers using levelling up funds.

It did not go down well with green campaigners and smaller-scale fishers, as reported in the Guardian [18]:

““It will be good for the big boys who already make shitloads of money,” said Tristan Northway, who skippers a 9-metre fishing boat, Adela, and sells directly from the deck of his vessel. “But it will do nothing for the rest of us and nothing for the town.””

How to source sustainable fish

So, what do you do with all of this new-found knowledge?

Well, you help the ocean to recover and skippers to “level-up”.

You can do this by buying from fishmongers, rather than the supermarket.

Or by having fish from delivered directly to your door, from the likes of Sole of Discretion.

You can also sign this petition launched by Patagonia to end Bottom Trawling.

One thing not to do is read this and give up! Don’t just buy any old fish because you think ‘it’s all the same’ and you can’t trust anyone. You can. We’ve shown you how here.

Where to buy sustainable seafood…

Here’s our top two favourite brands for buying genuinely sustainable fish.

Sole of Discretion

Fresh fish, fished to the highest ethical standards.

Inspiration for other fish species to try

Generally small oily fish species are good – mackerel, sardines, anchovy, sprats, and herring. They are mostly abundant, quick to reproduce, and are rarely fished by bad methods in terms of by-catch or endangered species.

Probably, the most sustainable seafood you can eat is mussels. They passively grow on a rope so you can go wild for Moules Frites.

Fresh fish inspiration for spring and summer

Spring is a good time to start to enjoy really good Founder, Plaice and Dover Sole as they are starting to fatten up.

They get thinner as we head into winter because this is when they spawn, which uses up a lot of energy.

Fresh fish inspiration for autumn and winter

Mussels

Oysters

Crab

Squid

Pollack (good cod alternative)

Ray (similar to skate)

Huss (a meaty white fish from the shark family. Choose Spotted Dogfish over the threatened Nursehound – great for stew, fish curry and tacos)

Read more…

Sustainable

Tuna

Sustainable

Prawns

Sustainable

Salmon

References:

[1] https://europe.oceana.org/impacts-bottom-trawling/

[2]https://www.wwf.org.uk/what-we-do/planting-hope-how-seagrass-can-tackle-climate-change

[5] https://www.wwfmmi.org/plastic/?uNewsID=6393966

[6] https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?361757/WWF-Statement-on-MSCs-Lack-of-Reform

[8] https://marinestewardshipreview.org/

[9] https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/global-industrial-fishing-footprint-spd/

[10] https://www.msc.org/about-the-msc/our-funding-and-finances

[11] https://seas-at-risk.org/publications/bottom-trawling-climate-change-and-the-oceans-carbon-storage/

[12] https://www.wwf.org.uk/what-we-do/planting-hope-how-seagrass-can-tackle-climate-change

[13] https://www.openseas.org.uk/evidence/

[14] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/faf.12209

[15] https://ejfoundation.org/resources/downloads/ejf_prawn_consumer_guide_new_ok.pdf

[16] https://www.itfglobal.org/en/reports-publications/one-way-ticket-labour-exploitation

[18] https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/aug/28/row-over-brixham-fish-market-levelling-up-plan

All illustrations: Sophie Dunster, Gung Ho Studios