The best sustainable men’s activewear for the gym, hiking, swimming and more…

The high street talks a good game when it comes to conscious fashion, including Primark on ethics and H&M on sustainability. But is the high street walking the walk? Well, it’s complicated.

Or is it?

These brands want you to believe it’s complicated but it’s actually very simple.

So this is the issue: there’s just one thing that all high street brands have to do to be more sustainable. *Drum roll please* They have to make less stuff. Yup. Sell less clothes. That’s it. Job done.

They’re instantly more sustainable because they are not selling us more of what we don’t need.

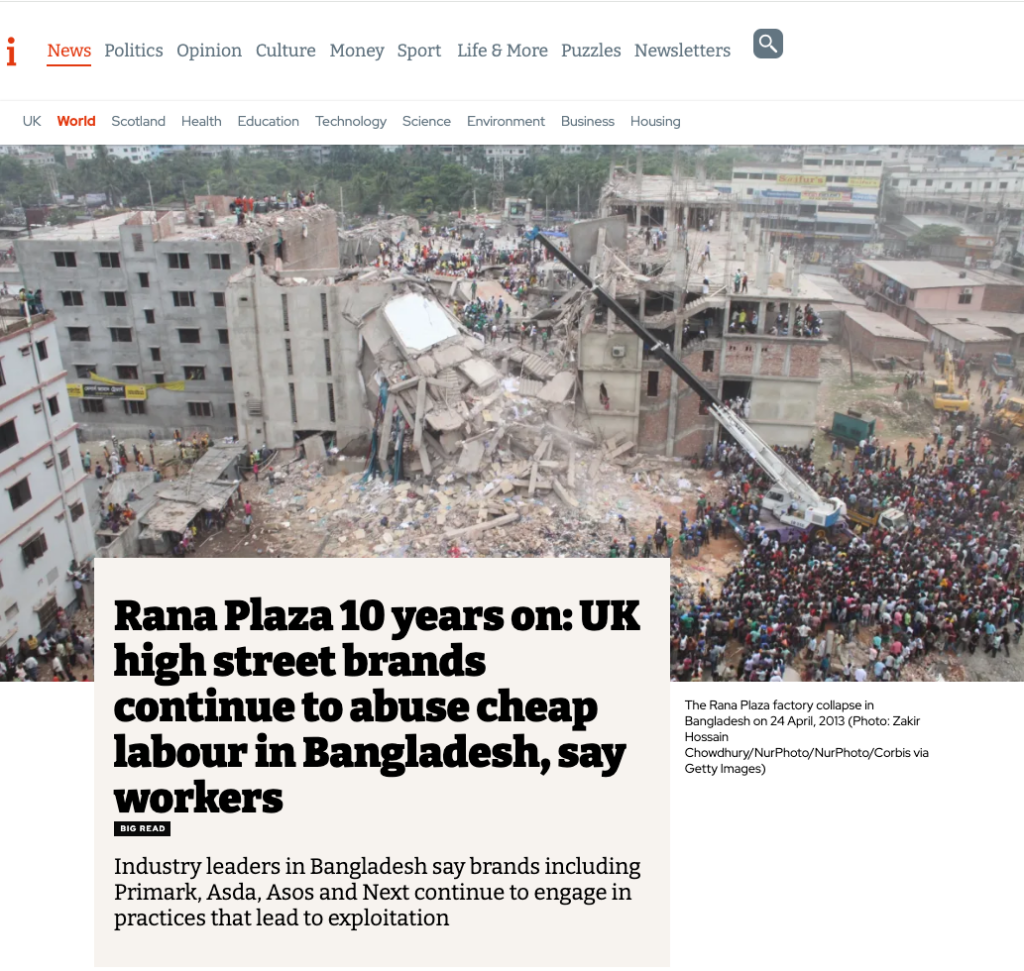

To be more ethical they also need to stop abusing their workers, which they’ve been working towards for more than 10 year nows, especially so since the factory Rana Plaza collapsed in 2013.

(Scroll down to the heading ‘Primark’s ethics: is Primark any different to the likes of New Look, Zara or Bond Street?’ for more on Primark specifically. This first part is a super-fast intro to the problems with super-fast fashion…)

The buy once, wear once model

Of course, this is a hard truth to acknowledge. Retail therapy is an actual thing for a reason: that sense of satisfaction you get from buying something you totally love ‒ just to wear it once. This means a mammoth 11 million items of clothing end up in landfill each week.

Thanks to the rise of fast – or throwaway – fashion in the UK, we’re now buying twice as many clothes than we did a decade ago, and more than any other country in Europe.

Plus, there’s all the garments that are being made and not sold. The Guardian reports that “between 80 billion and 150 billion garments are made every year and that between 10% and 40% of these are not sold. So it could be 8 billion or 60 billion excess garments a year.”

Fashion’s biggest success

For fashion’s most successful coup is to distract us from the devastation and waste that lay in the wake of its beautiful designs. The stats of environmental damage are staggering.

In 2019, the UN reported that fashion is the second most polluting industry in the world. Despite this stat being highly controversial, the impact of the industry is in little doubt. It is responsible for more carbon emissions than all international flights and maritime shipping combined.

It takes between 7,500 – 15,000 litres of water to make a single pair of jeans. At the lower end, this is equivalent to the amount the average person drinks over seven years, yet we keep our clothes on average for just two years.

You can’t really have a problem with cotton, can you?

So-called natural materials are not as harmless as we have been led to believe. Cotton, a thirsty crop grown with huge amounts of pesticides, is accused of being one of the primary causes of Central Asia’s Aral Sea – once the world’s fourth largest sea – drying up.

Leather is said to be one of the causes of the 41,000 fires to ravage the Amazon from January to August 2019.

Synthetic – or vegan – materials, derived from the oil industry, fare no better for reasons of production and upkeep. Washing synthetic clothes leads to 500,000 tonnes of microfibre – equivalent to more than 50 billion plastic bottles – being dumped into the ocean every year. That’s harmful to fish and sea life. And it’s finding its way into our bodies, too.

To be clear, every high street brand and online brand is doing this. You may think Rita Ora’s collaboration with Primark looks like a good thing.

But, there is so much devastation behind those photos, it’s unreal.

Is that dress really worth all that destruction we just told you about? Does it still look as beautiful now you know?

That’s up to you to decide. To buy or not to buy: that should always be the question.

Sustainable fashion brands Live Frankly recommends

Explore some of our favourite slow-fashion brands who are working hard to create a fairer, more sustainable fashion industry for all:

Project Cece

Project Cece is the largest online marketplace in Europe for sustainable fashion.

Project Cece is proving that shopping for sustainable clothing can be easy, fun, affordable and for everyone.

Rapanui

Rapanui is a brand for adventurers. It sells trendy and durable outdoor clothing that won’t break the bank.

On a mission to reduce waste, Rapanui offer free repairs, and everything is made to order in its green-powered factory.

WAWWA

WAWWA is a unisex clothing brand that sells a range of trendy outerwear and streetwear.

From the offset, WAWWA have focused on only creating clothes in a more planet and people friendly manner.

Primark’s ethics: is Primark any different to the likes of New Look, Zara or Bond Street?

To get back to the other question of whether Primark is worse when it comes to ethical trade and environmental sustainability.

Primark is one of the biggest fashion retailers when it comes to its volume of stock. So, in this sense, yes they are worse.

But, when it comes to the materials or the chemicals they’re using to dye their clothes, they’re not necessarily any worse or any better. This is because brands all use the same factories.

“I can tell you who on Bond Street shares a factory with us.”

Paul Lister, Primark

Yes, you read that correctly.

People often call Primark’s ethics out first because it is one of the cheapest brands. But, several years ago I interviewed the head of Primark’s Ethical Trade Team, Paul Lister, and he told me that Primark shares 98% of their factories with other brands.

READ MORE

“I could walk down Bond Street and tell you pretty much who on Bond Street who shares a factory with us,” says Lister.

The problem is, although all brands have ‘Codes of Conduct’ these are rarely worth the paper they are written on. This is because factory owners will sign, but not necessarily follow, the international labour agreements.

I asked Lister: “You’re genuinely comfortable with the conditions in these factories?”

His response was: “It’s a developing world question. If you accept the developing world, you have to accept, in my view, the risks in buying anything from the developing world…

“We have a code of conduct based on the Ethical Trading Initiative code of conduct. It looks at working hours, child labour, forced labour, health and safety at work.

“Each factory signs up to the code of conduct. Does that mean they adhere to the code of conduct? Well, no, clearly because we wouldn’t have any questions [if they did].”

At the time he said Primark was working with around 1,700 factories and he said they had a team of around 100 auditing and checking the factories to look for improvements.

In 2024, they are reporting that they have 851 factories and 130 people auditing them. It’s arguably better, but it’s almost certainly not enough.

Why are brands sharing factories?

Brands share factories because they all benefit from economies of scale. Plus, they never have to accept full responsibility for the people who are making clothes for them. It’s the factory owner’s fault you see, not theirs for pushing down prices, making last minute changes to orders or refusing to pay for clothes that have been made and they don’t want any more…

The human cost of fast fashion

This has a huge impact when it comes to the garment professionals. While the dream of having access to a constantly revolving wardrobe has great appeal, the human cost is arguably the most scandalous thing about fashion.

“There’s a structural violence against women that has become normalised in society, and it has become normalised inside the factories, as well.”

Lalitha Dedduwakumar, Member of the Women’s Leadership Committee of Asia Floor Wage Alliance and Chief Organiser of Textile Garment and Clothing Workers Union

It’s estimated that up to 80% of garment workers are women and their plight is fundamentally linked to the oppression of women in patriarchal societies.

There is little regard for their safety and even less value placed on their work, and brands are exploiting this for cheap labour. Meanwhile, fashion advertising – such as Primark’s latest ‘adaptive underwear range’ and Adidas #SupportIsEverything campaign showcasing naked breasts – dubiously suggests they are allies in women’s empowerment.

Fashion’s gender-based violence crisis

The ‘A Stitch in Time Saved None: How fashion brands fuelled violence in the factory and beyond’ report published by labour rights group Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA), reveals a very different story.

It explicitly states: “Brands rely on the secondary position of women in society to keep costs low and amass super-profits by paying poverty-level wages.”

The report documents how this is not simply a case of brands looking the other way and pretending not to know. It’s endemic to their business model:

“Brands are able to dictate the terms of production, requiring ever higher production targets at ever lower rates, leading to high-pressure work environments in which management, who are typically men, employ tactics like bullying, abuse, and harassment to speed up the work process and discipline the predominantly female workers.”

Connecting the dots, it reports that this economic insecurity leads women to tolerate or refrain from reporting unwanted and abusive behaviours – especially as this may lead to outcomes that put them in even more precarious situations.

Primark ethics: Transparency

At the time of the interview, Primark wasn’t publishing the names of the factories they work with.

In 2022 Primark was more transparent, listing 902 factories across 26 countries on its website.

They say this makes up 95% of the factories that produce their products in-store.

In 2024, this has gone down to 851 factories across 22 countries, accounting for approximately 94% of their supply chain. The map doesn’t work.

It’s also important to note this doesn’t account for the whole supply chain:

They don’t account for the farmers who produce the cotton, for example. Nor do they include the factories that weave this cotton into materials. For all fashion brands, the supply chain is a lot more complicated than everything being produced in one factory and sent straight to store.

The ‘unseen’ people at the bottom of the supply chains, the cotton farmers, for example, are at risk of being even more exploited.

Why transparency is important

Transparency doesn’t necessarily mean an ethical supply chain. It probably makes you feel better as a customer. But, it doesn’t give you any insight into how this factory really operates. It doesn’t tell us the ratio of male to female management, for example. Or, if the workers have access to trade unions.

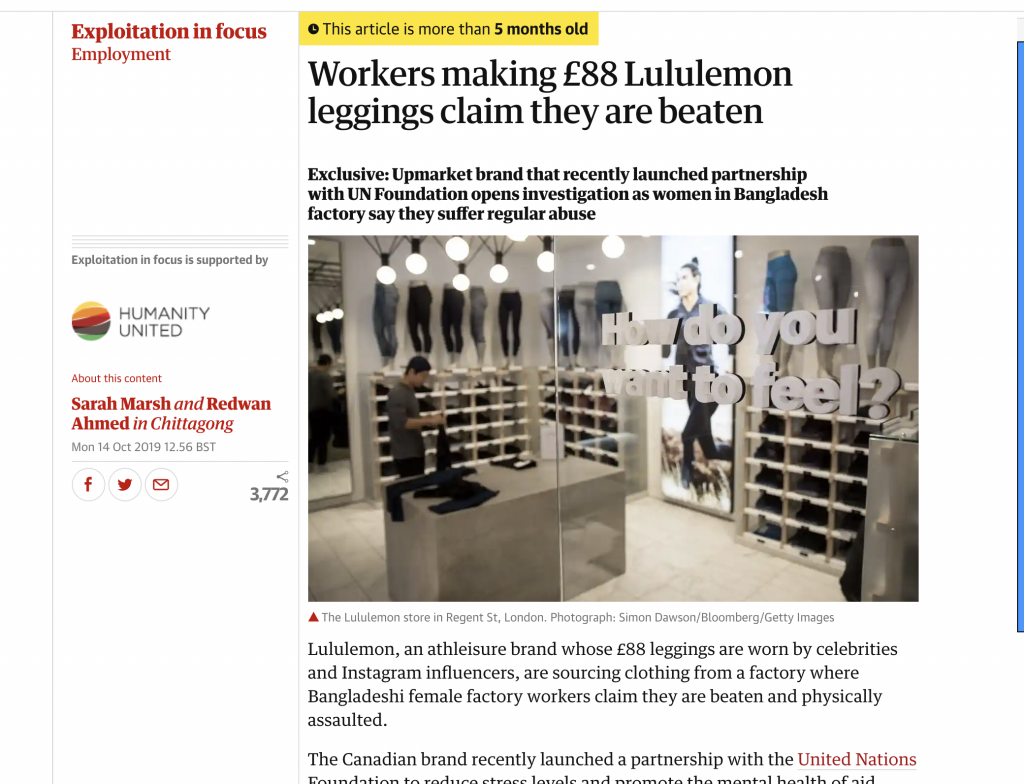

Two unrelated Primark examples of this include: An investigation published in the Guardian in which garment workers making £88 Lululemon leggings say they suffer regular abuse. And reports of bosses forcing female workers to commit sex acts to secure working contracts. The brands implicated include Levi, Wrangler and Lee.

One testimony said: “All of the women in my department have slept with the supervisor. For the women, this is about survival and nothing else. […] If you say no, you won’t get the job, or your contract will not be renewed.”

The report explicitly implicated the brands for their failure to detect these violations. They have voluntary codes of conduct and monitoring programs, yet the abuses continued.

So, transparency is important because when companies publish this information it helps NGOs, unions and local communities to stand up to human rights and environmental issues. It means these stories have a chance of making it into the press. It gives otherwise invisible and silenced workers a platform to speak out.

Primark ethics vs our ethics

I also asked Lister: “You’re working with the developing world and accepting the issues that are there but you’re also profiting from that? Then you’re paying for audits which is probably a lot cheaper than paying your own factory…?”

Before you nod your head sagely in agreement, as I hope you will, please take a second. Consider that these brands only exist because we buy from them. Every customer is also profiting. We could choose to buy from more sustainable brands.

Lister said: “Unashamedly we are making a profit… but the workers are also being paid. In some countries this is the beginning of industrialisation.

“The alternative in Bangladesh has always been subsistence farming or early stage industrialisation.

“Your question to me would be don’t exploit them… and I fundamentally 100% agree with that.”

A living wage

Except, workers are exploited, the world over.

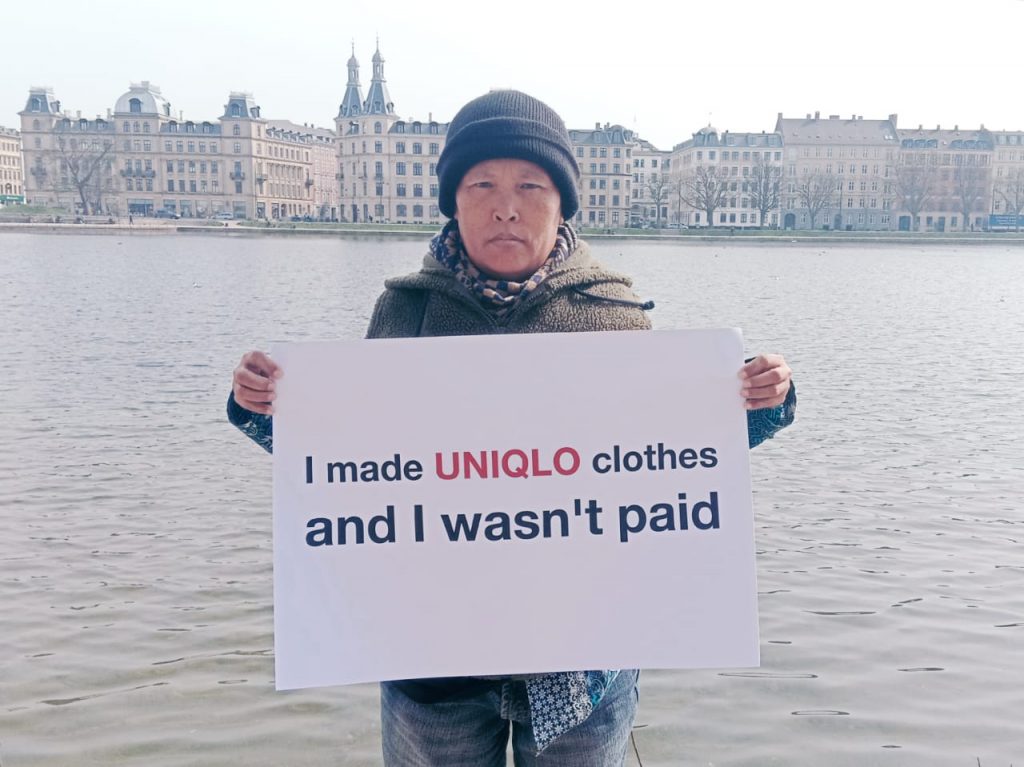

Arguably, even more so during the COVID-19 pandemic when $3 billion worth of garments were initially paused or cancelled by the biggest fashion brands, globally, affecting millions of workers.

This ‘wage theft’ has been well documented. Headlines across the world called out brands. The BBC reported how New Look is delaying supplier payments indefinitely. At one point they were making £160,000 a day.

Primark was making £650 million a month. The BBC also reported Primark has said they will set up a fund to ensure workers who make their clothes are paid. However, details around how this will be put into practice were suspiciously hard to find.

On the website, details of the extended refund policy and all the clothes they’re so generously donating in Europe were very easy to find.

Vogue Business highlighted how suppliers in countries like Bangladesh and Cambodia were vulnerable even as companies like H&M and Inditex promised not to cancel existing orders. This is because of a nifty little clause in the contract that means brands don’t pay for orders until they’ve shipped. Guess what? With shops closed, shipments weren’t shipping.

“Cancelling the goods or not taking the goods — for my workers, it is the same. The worker is not getting the money,” said Mostafiz Uddin, a denim factory owner in Bangladesh.

At the time it was published, ‘The Fired, Then Robbed’ report by the Workers Rights Consortium (WRC) estimated that at least $500 (£360) million severance pay was still owed to the millions of garment workers who lost their jobs due to the pandemic across the globe.

This equates to an average of $1,000 (£720) per garment worker – equivalent to five months’ wages. As such, the WRC reported that more than two-thirds of workers or members of their household skipped meals or reduced their quality. Workers were forced to choose between going hungry and going deeper into debt. At the same time, online fashion sales soared and fast fashion shops reopened to queues that extended down the street.

Primark ethics: the conclusion

So, to answer your original question. Primark’s ethics are about the same as most high street brands and online fashion retailers. They are all still putting profits ahead of people and the planet. At this stage, putting them in a league table feels a little pointless.

In their 2023 annual report, Primark’s owners boast they are “one of the fastest growing fashion retailers in Europe”. They say they have “the highest sales by volume in the UK and a growing presence in the US”. Their revenue was more than £9m (up from £5.6m in their 2021 annual report) with a profit of £735m (up from £415m in their 2021 report).

The fashion industry generates an estimated £1.5 trillion a year.

So, when a sources close to Primark claim: “Primark is working hard to become a more sustainable business and is working hard to improve its clothes and the lives of women in its supply chain,” it rings a little bit hollow.

When they say: “Primark is pursuing a living wage for workers in the supply chain”, this means they are choosing to profit from exploitation in the meantime.

The fact that Primark has been a member of the Ethical Trading Initiative since 2006 and have achieved the top level “leadership” status since 2011, is quite frankly, horrifying.

If this is leadership, what is the rest of the industry up to?

Main image: Photo by El gringo photo